How do you rate your wine drinking preference? Conservative, tried-and-trusted, varied or adventurous? I’ve always thought of myself as pretty adventurous, until I discovered “Vins Insolites” (unusual wines), a new book by the French journalist Pierrick Bourgault.

Bourgault’s impressive opus catalogues 20 years of travel and research, to bring together 50 vinous curiosities. They include a dessert wine from the Gobi desert, 15 meter high vines in Portugal, Aleš Kristančič’s “DIY” non-disgorged sparkling wine and a continuously harvested vineyard in Indonesia.

These are, for most I suspect, totally unknown and seriously obscure. But not all of the globe’s less discovered wines are so hard to find. In 2015, I visited two Balkan countries, and tasted wines from most of their neighbors. Bulgaria’s wines used to be better known before the fall of communism, although it’s now experiencing something of a quality wines renaissance. There’s more to be said about Bulgaria in a future article.

These are, for most I suspect, totally unknown and seriously obscure. But not all of the globe’s less discovered wines are so hard to find. In 2015, I visited two Balkan countries, and tasted wines from most of their neighbors. Bulgaria’s wines used to be better known before the fall of communism, although it’s now experiencing something of a quality wines renaissance. There’s more to be said about Bulgaria in a future article.

Bosnia’s wine industry, on the other hand, remains willfully obscured. I suspect this has much to do with a country which, while often stunningly beautiful, is still ravaged by poverty and ethnic tension. Neighboring Croatia has made a considerable impact on the international wine market, and was accepted as a member of the European Union. Bosnia still feels a long way from Europe, with a very evident east/west mix, especially in Sarajevo.

The more western, largely Christian population has a long history of wine production, dating back to Roman times at the very least. Coupled with the existence of a few uniquely indigenous grape varieties, I was pretty sure I’d find something interesting to drink over the course of a week’s holiday.

Challenges

There was no shortage of vineyards and producers, but traveling in a country that still lacks a modern wine culture has its frustrations. In most regions where wine is part of the fabric of daily life, you can sample a selection in restaurants, wine bars, shops – not to mention visiting the producers themselves. Not so in Bosnia.

Locals still tend to produce their own wine, and balk at paying high prices for bottles. That situation is beginning to change, but it can be challenging to find anything interesting to drink when eating out. Bosnian cafes and restaurants are in love with “individual serving” 200ml bottles, of the sort most often encountered in-flight. Even with reputable producers, these receptacles are depressingly often oxidised, I assume through poor storage and poor bottling. Beware of anything on a list that looks like wine by the glass, if it comes in one of these horrors.

Wine bars are beginning to pop up, but may not deliver what you expect. The best is undoubtedly Vinoteka Dekanter in Sarajevo, with an excellent selection of local wines by the glass and bottle. A brave venture in Mostar only offered one wine – a Chardonnay – by the glass. During our visit, all the other customers were drinking coffee, perhaps Bosnia’s most important beverage.

The concept of wine tasting isn’t universally understood. Randomly visiting a large, professional looking winery, we were informed that we were welcome to taste the wines, but we’d have to pay for the entire bottle since there was no “by the glass” pricing. Luckily, I discovered a number of smaller producers who were more obliging.

Regions

Bosnia has two main wine regions – and a wine route that links them up. Signs are wildly inconsistent in their spacing, accuracy and concurrency, but they are there. The bucolic hills around Mostar and Medugorje interested me above all else. Two indigenous varieties dominate here – nutty, perfumed Žilavka, a white grape of such potential that you wonder why it isn’t better known, and soft, approachable Blatina, a red unisexual variety that seems to keep its acidity well in the scorching Herzegovinian summer.

It’s worth putting up with the scruffy streets of religious tat otherwise known as Medugorje – an apparition seen by six teenagers has transformed this backwater into a huge Catholic theme park. Many of the best wineries are clustered around here, in the villages of Čitluk, Ljubuški, and Capljina. Josip Brkic and Josip Marijanović are two bright stars who between them make the best examples of Žilavka I’ve tasted.

Heading South towards Dubrovnik, you get to Trebinje, the epicentre of the second wine region. The climate is noticeably hotter here. It therefore puzzles me why Vranac is so popular. This thin-skinned red variety oxidises in a heartbeat, and many wines have a telltale porty note. The best and freshest example I tasted was from Anđelić, a good producer based on the outskirts of Trebinje.

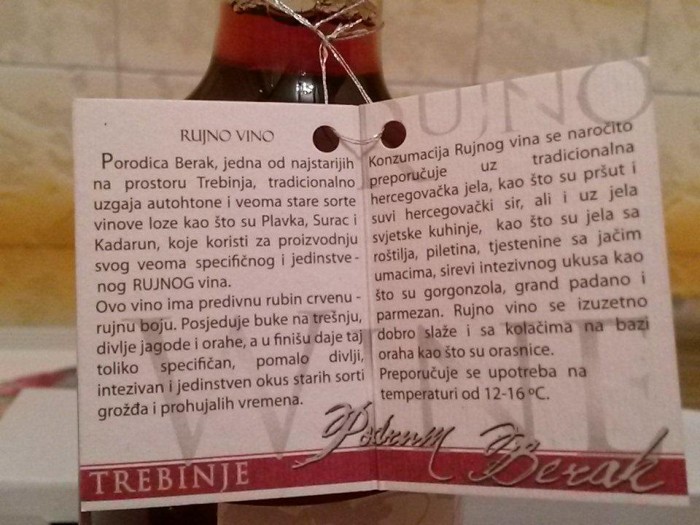

I cherished my final visit, to Alexander Berak’s cellar in a Trebinje suburb. Their Žilavka was fresh and welcome on a very hot day, but a rosé blend “Rujno Vino” got me seriously excited. Made from not one, but three rare varieties, this blend of Surco, Kadarun, Plavka was savory, complex and unique. A level of obscurity that might even get Pierrick Bourgault’s attention.

I cherished my final visit, to Alexander Berak’s cellar in a Trebinje suburb. Their Žilavka was fresh and welcome on a very hot day, but a rosé blend “Rujno Vino” got me seriously excited. Made from not one, but three rare varieties, this blend of Surco, Kadarun, Plavka was savory, complex and unique. A level of obscurity that might even get Pierrick Bourgault’s attention.