Piedmont’s other red grape comes onto the world market with a new, colorful cast of winemaking characters. This is the first in a two-part series on Ruchè this week on Palate Press.

For lovers of obscure wine finds, the sleepy little town Italian town of Grana might be the next destination to pull up on Google Earth. This town provides a scenic view of the growing area for Piedmont’s most unsung red wine grape varieties: Ruchè. For most of its hundred-year history, Ruchè has been about as sleepy as Grana. Until very recently, when a diverse group of characters decided to jump-started its new popularity.

The ruchè grape has a limited picking window, prevalent tannins, vigorous vegetation, and is prone to both sunburn and high potential alcohol. Difficult to farm and even more difficult to vinify, wines made from Ruchè were thought not to be age-worthy material, and it was all but abandoned by the 1980s.

But it’s hard to keep a good grape down, and the wine is tastily food-friendly. In the last several years Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato has been on the comeback trail, albeit still in a modest form, achieving Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status in 2010. With very low production numbers this wine is not an easy find; about 700,000 bottles are made annually, and only 30% of that is exported. A slight majority of the exports goes to the U.S., where the wine does well on the East Coast restaurant and small wine shop scenes. And for those looking for something different, it’s hard to get more “different” than a glass of Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato with dinner.

The cadre of Monferrato winemakers who are trying to make a new name for Ruchè in the fine wine market are just as colorful and interesting as the grape itself. Their sense of camaraderie, healthy competition, shared passion (and eccentricities) are reminiscent of the energies propelling producers in areas such as Lodi and Livermore, whose efforts to have their regions be seen as fine wine contenders are starting to gain traction in the U.S.

Dante Garrone

Soft-spoken Dante Garrone has a fondness for history. His cellphone ringtone is the theme from Raiders of the Lost Ark, and he counts Egyptology as one of his major hobbies. Small wonder, then, that he would describe Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato in historical context: “the story of Ruchè is new and old, at the same time,” he told me when we toured his small family winery.

Garrone Evasio & Figlio was founded in Grana by Garrone’s grandfather Evasio Garrone, in 1926. When the nearby railroads were destroyed during the Second World War, an undeterred Evasio started selling wine in Lombardy by bicycle, delivering final orders by truck – or sometimes by horse-drawn cart. The winery is now run by Marco and Dante Garrone, who produce about 3,300 bottles of Ruchè annually, from what they describe as “typically old” vines (averaging about thirty years). Garrone is fond of using old concrete tanks for Ruchè vinification, dating from the 1970s.

Garrone offers what might be the most populist Ruchè bottling. Despite a very difficult vintage, their 2014 Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato is instantly likeable; aromatic and peppery, with bright red fruit aromas, and hints of grapefruit rind and flowers. The mouthfeel is fleshy, very spicy, robust, and smooth, with just enough rustic, rough-around-the-edges quality to give the wine some additional personality.

Marco Crivelli

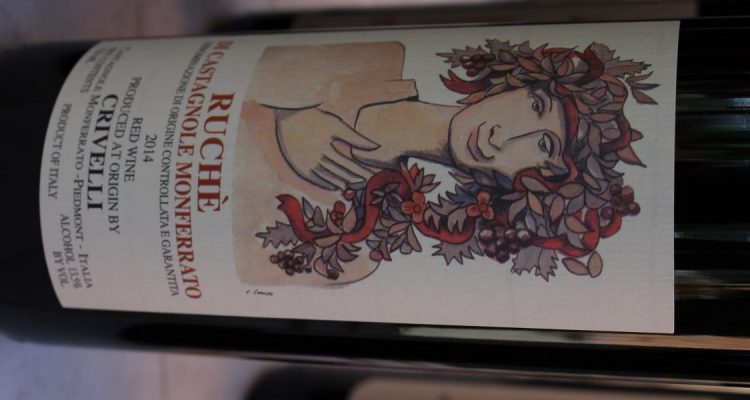

If the modern Ruchè movement has an elder statesman, it’s the wild-haired, wild-eyebrowed, and wildly opinionated Marco Crivelli. Crivelli (who now operates his winery with his son) was one of the first to export Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato to the U.S. His great-grandfather Secondo settled in the area around 1860, and set the stage for the family’s future by purchasing hilltop vineyard land that later proved to contain some of the best sites in the area for growing grapes (and for panoramic views; a total of twenty-two bell towers are visible from one of their vineyards). Crivelli’s father and grandfather took up grape growing, purchasing more hilltop land that “no one wanted.” The limestone, sand, and chalk-laden clay proved so heavy that “even the horses slipped,” he recounted to me.

The soil was just about perfect, however, for grapes, and he now farms five hectares of estate Ruchè vineyards, with vines that are a about thirty years old. Crivelli, describing himself as a “perfectionist,” seems hell-bent on producing the region’s most authentic Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato, eschewing herbicides (“do you want to make chemical wine, or real wine?” he asked me hypothetically), using minimal sulfur dioxide, and producing one bottling of Ruchè, rather than tailoring styles for different markets. “I don’t sell wine,” he insists. “I make wine.”

Crivelli’s approach might be obstinate, but it’s also successful: his 2014 Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato is excellent, starting with an exotic, spicy nose, with aromas of fresh red berry fruits and roses. A delicate entry glides into a slightly astringent bite in the mouth, with spices and flowers lingering throughout.

Pierfrancesco Gatto

During harvest, the short but powerfully built Pierfrancesco Gatto, who runs Azienda Agricola Gatto Pierfrancesco, has hands that are perpetually stained a dark purple from picking and pressing eleven hectares of grapes. His family’s winery building was built before 1900, when his grandfather would take wine by horse to sell in the city of Milan. Pierfrancesco started his stint with Ruchè in 1993, producing about 2,000 bottles. His Castagnole Monferrato winery now makes about 65,000 bottles of wine per year, about half of which is Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato, exporting to the U.S., Canada, Japan, Australia, Tasmania, Hong Kong, and across Europe.

While probably not a long-term ager, Azienda Agricola Gatto Pierfrancesco’s 2014 Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato is one of the more elegant and complete interpretations of the grape that you’re likely to find. Its dark ruby color is gorgeous, as is its nose of violets, roses, black pepper, grapefruit, and red berries. It’s spicy, smooth, and delicious now, with tannins that anchor a lively dance on the palate.

Luca Ferraris

Luca Ferraris’ 18 hectares of vineyard holdings, and his winery’s approximately 80,000 annual bottle production of Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato, make him the largest Ruchè grape grower and producer in Asti, and, by extension, in the world. It’s fitting then, that he is also Ruchè’s most prominently vocal proponent, particularly when it comes to debunking the grape’s age-worthiness (“the idea that Ruchè cannot age… it’s wrong, totally wrong,” he told me; proving it by serving an earthy, and still fresh 2004 Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato Classic from the family cellars).

Luca Ferraris’ 18 hectares of vineyard holdings, and his winery’s approximately 80,000 annual bottle production of Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato, make him the largest Ruchè grape grower and producer in Asti, and, by extension, in the world. It’s fitting then, that he is also Ruchè’s most prominently vocal proponent, particularly when it comes to debunking the grape’s age-worthiness (“the idea that Ruchè cannot age… it’s wrong, totally wrong,” he told me; proving it by serving an earthy, and still fresh 2004 Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato Classic from the family cellars).

Improbably, Ferraris owes his vineyards to the California Gold Rush. His great-grandfather Luigi struck gold during the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s, which later enabled Luigi’s wife to purchase the Via al Castello house that would house the first family winery, established by Luca’s grandfather. Though Luca’s father moved to Turin in search of work, he continued to tend the family vineyards and sell grapes to the local cooperative. Luca took the reins of the winery and land in 1999, and started to modernize the production under the family’s label, eventually even partnering with Bonny Doon’s Randall Grahm.

Ferraris is the boundary-pusher of the region when it comes to Ruchè. To honor his grandfather, Luca decided to produce a full-on, amped-up Ruchè meant specifically for aging – or, alternatively, for a big steak dinner: Opera Prima per il Fondarore, a single-vineyard release from Castagnole Monferrato. The recently-released 2012 Opera Prima was aged 24 months in 500-liter second year oak tonneaux, in the family’s tufo cellars. At about 15.5% alcohol, it’s a robust, full-bodied, and demanding take on Ruchè. It’s quite young now, but still offers ripe, dark fruit flavors, black licorice, violet, and spice aromas, and a powerful, underlying tannic grip.

While the above might constitute the more colorful characters behind Piedmontese Ruchè production, they’re by no means an exhaustive list of the interesting reds being made from the grape. Other standout producers in the region include: Cantina Sociale, the regional cooperative; Bersano, which is better known for high production of Barbera; Tenuta Montemagno which has perhaps the area’s most modern take on Ruchè; Poggio Ridente, headed by Cecilia Zucca’ and Il Vino dei Padri, whose current owner repurchased the vineyards that his father once sold to fund his education.