I’d only been in the region a few hours. I was tired and jetlagged after twenty hours of travel and a nine-hour time difference. But our guide at the museum, our first stop, decided to wake us all up by giving us a playful quiz – an activity to awaken our senses. We were handed several cups to smell, each one offered a different scent that we were asked to identify. Caramel, one writer suggested. Another offered chocolate. I thought vanilla, or milk chocolate, or perhaps some kind of combo of both? It had a sweet smell to it. The answer? White chocolate. The next cup I identified as smoky. The answer was leather. Close. Another cup reminded me of French onion soup. The answer was simply, onion. And thus began a discussion of the whole idea of sensory experiences and triggers that remind us of certain scents.

This activity is common in wine tasting; identifying aromas often found in wine. But we weren’t there to taste wine. We were there to taste cheese, Comté cheese to be specific.

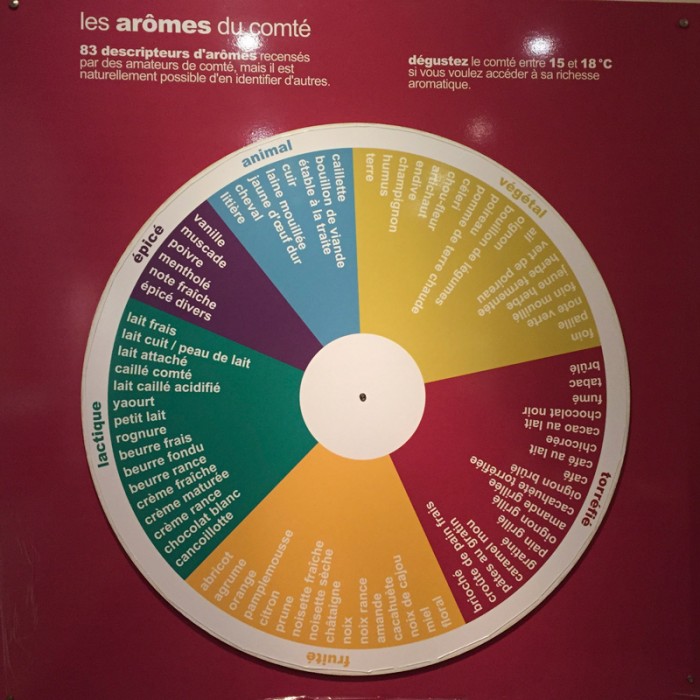

Like The Wine Aroma Wheel, created by Ann C. Noble, that many wine enthusiasts are familiar with, there is also an aroma wheel to help consumers identify those traits found in Comté cheese – over eighty flavor descriptors are included on the wheel, divided into six categories: lactic, fruity, roasted, vegetal, animal, and spicy. Are you kidding me, I thought, this is cheese we’re talking about! But I came to discover that this cheese has just as rich a history and strict standards of production as the wine regions surrounding it. This cheese, like the most important wine regions of France, has true terroir.

We were in the Jura mountain region in eastern France close to the border of Switzerland, as guests of The Comté Cheese Association, learning what makes Comté unique and complex.

We were in the Jura mountain region in eastern France close to the border of Switzerland, as guests of The Comté Cheese Association, learning what makes Comté unique and complex.

If I didn’t know better I would think I was still back in Oregon. The landscape is deeply green, vast, and mountainous (only lacking the dramatic peaks we have in Oregon). The climate is cool and it rains often. During my stay in mid-May, we started the week with bright and sunny temperatures in the low 80’s Fahrenheit – and ended our trip with rain, cold temps, and gray skies. Still, very Oregon-like to me. I now understand why so many Oregon winemakers were inspired by eastern France in the ’60s and ’70s to begin winemaking in a region where it was practically unheard of. But again, we’re not talking about wine. And this region is closer to the size of Rhode Island than it is Oregon; expanding approximately 570,000 total acres. Up in this lush green mountain region is where Comté’s history begins, over 1,000 years ago.

Like wine regions of France, the famous cheeses of France are also based on an appellation system, PDO (or “Protected Designation of Origin”) enforced by the European Union, and Comté is the highest-consumed PDO cheese in France. One of the first cheeses to receive a PDO status (or AOC, its original designation), in 1958, Comté has some seriously strict standards of production, all meant to preserve the tradition of the region and express its unique terroir. Let’s start at the beginning.

What is Comté?

Comté is a raw milk cheese made from the milk of pasture-fed cows, similar to Gruyère. The production involves three steps, beginning with the farms. And just like the cliché wine saying, “All great wine begins in the vineyard,” here all great Comté begins in the pastures.

Step 1: The Dairy Farm

There are roughly 2,700 small dairy famers in the region that produce the milk for Comté, and by PDO rules, only Montbéliarde and French Simmental breeds are allowed in the milk production. There are several items prohibited from the cow’s diet, GMO’s included. Each cow, by law, is required to have a minimum of 1 hectare (or 2.5 acres) of natural pastureland to graze. So if a farmer has 40 cows, he or she is required to have at least 100 acres of land for the cows to wander about. If California has happy cows, these cows must be ecstatic.

Walking through the pastures in late spring you can begin to imagine what the resulting milk will be like. The air is clean and crisp, with aromas of dry grass and spring flowers. During the summer months this is what the cows are grazing on, and all of these elements will present themselves in the resulting milk. In the winter the cows eat dry hay, produced from the summer grasses of the same farm.

Walking through the pastures in late spring you can begin to imagine what the resulting milk will be like. The air is clean and crisp, with aromas of dry grass and spring flowers. During the summer months this is what the cows are grazing on, and all of these elements will present themselves in the resulting milk. In the winter the cows eat dry hay, produced from the summer grasses of the same farm.

The cows are milked once in the morning and once in the afternoon, and the milk is then picked up by the fruitière (cheesemaking facility), were it will soon become cheese.

Step 2: The Fruitière

By law the milk must be turned into cheese within 24 hours of milking. This means Comté is being produced every single day of the year.

The term “Fruitière” is derived from the Middle Ages when farmers would produce the cheese as a way of preserving the milk, or the “fruit of the farm.” Back then, the cooking and pressing of this raw cows milk cheese was a way of preserving the milk of the region. Because it takes so much milk to make one wheel of Comté cheese (about 120 gallons, the equivalent of the milk of around 20 cows in a single day, milked twice), farmers would rely on neighbors to collaborate and share milk to contribute to the production of this cheese – one wheel of this cheese weighs in at 80 pounds and measures at 3 feet diameter. This co-operative approach is what Comté is based on today.

There are 160 Fruitières in the region, and in order to produce a true Comté cheese, it is not possible for one single farmer to produce his own Comté; the milk is combined with other farms and mixed in the traditional manner, as a way of protecting the microflora of the region.

The milk arrives at the Fruitière at 12 degrees Celsius (53 degrees Fahrenheit) and is placed into a copper vat. It is then warmed up to 24 degrees C (75 F) to begin the process. A small amount of natural starter and rennet (lining membrane derived from the stomach of a calf) are added to create the curds.

The milk arrives at the Fruitière at 12 degrees Celsius (53 degrees Fahrenheit) and is placed into a copper vat. It is then warmed up to 24 degrees C (75 F) to begin the process. A small amount of natural starter and rennet (lining membrane derived from the stomach of a calf) are added to create the curds.

Once it gets to the right consistency, which the cheesemaker knows by touch, the temperature rises again to around 54 degrees C (129 degrees F) where the cheese begins to solidify and separates from the whey, and is then cut into small bits. The room where this is all taking place in is around 115 degrees F. Not only is it an intensely hot environment to work in, it’s also around 95% humidity.

Once it’s ready, the cheese goes into the mold where it will rest for six hours as the remaining liquid is pressed out and the cheese begins to harden. Then it is removed from the mold and the exterior is washed in a salt and water solution and will move on to rest on spruce wood that must come from the region.

This next room is the opposite of the cheese making room. It’s much colder (around 60 degrees F) and smells heavily like ammonia from the walls and walls of fermenting cheeses stacked high. This smell is not for the faint of heart nor sensitive to strong aromas.

The wheels will remain here for about three weeks, getting washed by hand with salt and water a few times a week, until they are ready for the next step. Don’t let the salt solution lead you to think the resulting cheese is salty. It is not at all. The solution helps to create the thick exterior, which protects the cheese.

Step 3: The Affinage Cellar

The affinage is the maturing cellar where the cheeses go to age a minimum of 4 months by law, and up to 18-24 months, or longer – depending on the individual wheel. There are only sixteen aging cellars in the entire region housing the 1.5 million wheels of Comté cheese produced each year, and each affineur has his own aging technique that is dependant on the location, environment, and style of the individual affineur.

The affinage is the maturing cellar where the cheeses go to age a minimum of 4 months by law, and up to 18-24 months, or longer – depending on the individual wheel. There are only sixteen aging cellars in the entire region housing the 1.5 million wheels of Comté cheese produced each year, and each affineur has his own aging technique that is dependant on the location, environment, and style of the individual affineur.

It’s the affineur’s job now to determine when each wheel is ready to be sold and consumed. While the average is 8 months, you can find Comté anywhere from 4 months to 24 months, and even older.

Tasting Comté

The younger cheeses will generally be softer, fresher, with more lactic aromas of butter and yogurt, along with some fresh fruit and sweet caramel notes. The longer-matured cheeses will reflect more spicy, nutty, and intense notes. But, because of all the variables involved with Comté production, there is no standard to what you will expect from each type or age of cheese. They are incredibly varied.

And, as our tasting guide back at the museum told us, “You can’t taste the same Comté twice,” it is always changing. The taste varies based on several conditions (weather, what the cows eat, location, terroir, etc.).

Like grapes from individual vineyards, the milk from one farm will reflect different characteristics from the farm a couple miles down the road, and so on. Each cheese will be slightly different from the next.

Color and time of the year

Since the cows diet changes with season (pasture-fed during spring, summer, and fall, and hay-fed during winter), the milk too will change. What this generally means in the resulting cheese is that the summer cheeses are usually darker and richer in color, whereas the winter cheeses are much paler, almost white in color. Color, however, does not give you an indication of the cheese’s age.

Aged cheeses (12 months and older) will begin to develop small white crystals that look a bit like salt. But don’t confuse this with salt. These are amino acids, and the taste is crunchy, nutty, and delicious.

Aged cheeses (12 months and older) will begin to develop small white crystals that look a bit like salt. But don’t confuse this with salt. These are amino acids, and the taste is crunchy, nutty, and delicious.

Serving and Pairing Comté

Comté is like the sparkling wine of the cheese world. It is incredibly versatile and can be used in unlimited ways. Softer and more subtly, younger cheeses melt beautifully into dishes, whereas the older ones have intense aromas and a more solid texture which are delicious both cooked and uncooked.

Both young and aged Comté are fantastic for a cheese plate where you can explore the cheese uninfluenced by external flavors, but they are also perfect for cooking with. Practically anything that requires cheese you can use Comté for – from baked dishes, like macaroni and cheese, gratins, soufflés, tarts, to sweets like pastries and scones, to soups and salads, to grilled cheese, and even stovetop dishes like risotto. And don’t get me started on the fondue. Try taking three different ages of Comté and making a traditional cheese fondue. Add some morels for added flavor. Heaven. The day I came home from my trip I made a simple omelet with shredded Comté and fresh herbs, which was one of the best I’ve had in years. Even my picky four-year old twins devoured it.

And speaking of sparkling wine, Comté is a fantastic match for bubbles, whether Crémant du Jura – the traditional method sparkling wine of the region, usually made with primarily Chardonnay, and can also include a blend of Savagnin, Pinot Noir, and Trousseau – or your favorite dry sparkling from outside the region. The mix of fruity and nutty notes in the cheese is a winner with a dry sparkling. The older, more intense, nutty cheeses also pair seamlessly with the traditional Vin Jaune from the Jura. This is the prized wine from the region, which slightly resembles a fino Sherry because of its production methods – it is aged for six years in barrel under a layer of yeast on the wines surface, giving the resulting wine an oxidative and rich flavor.

Comté’s rich history, production standards, ties to regional land and people, not to mention the diversity of flavors found in this one style of cheese, and range of uses, truly make it a wine lovers cheese. At least one this wine lover can truly appreciate.

And as I think back to that aroma wheel I’m still astounded by the fact that it is possible to detect 80+ descriptors in one style of cheese. But then again the same can be said about a great wine.