It’s been said that you shouldn’t trust a vigneron if they don’t have soil under their fingernails. By that notion, I’m not sure what to make of Waterkloof‘s head winemaker Nadia Barnard when we meet at their commanding property in the windswept hills near Stellenbosch. Not only are her fingernails salon-perfect, she’s wearing strappy sandals and a rather ritzy outfit that doesn’t look like it could stand up to even an hour of battonage.

I put my preconceptions aside and listen. Nadia is in charge of an impressive operation – Waterkloof has 65 ha (160 acres) under vine, with another 30 ha (74 acres) about to be planted – and together with owner Paul Boutinot and vineyard manager Christiaan Loots she’s also presided over the conversion of the estate in its entirety to biodynamic farming, with Demeter certification awarded in 2015.

Barnard began her career working mainly with conventional farming methods. Does she notice a difference with the biodynamic approach? “Yes absolutely – the quality of the grapes coming out is incomparable. The fruit’s much more structured, with smaller berries but more intense flavours.” She also notes the ageing potential of the wines – “The proof is in the pudding – the wines keep longer, and develop really well.”

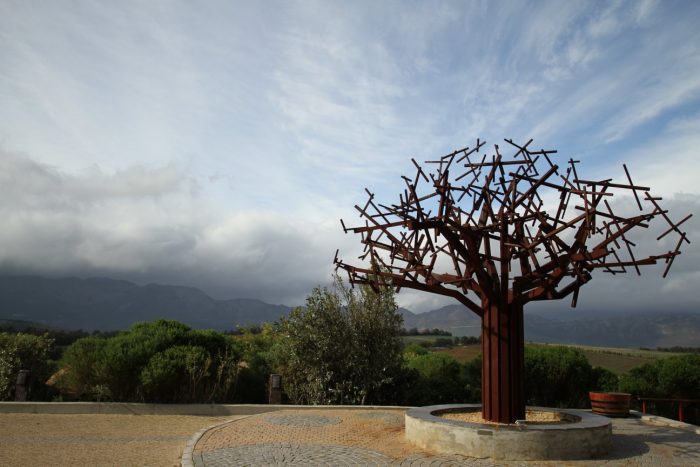

Waterkloof debunks the oft-heard, rather patronising claim that “it’s impossible to do biodynamics on a large scale”. All it takes is vision and, I suspect, fairly deep pockets to cover the initial investment. Boutinot clearly has both, for this is a grand and ambitious project, with a seriously upscale restaurant housed in the modernist winery building.

Biodynamics is not practised with half measures here. Waterkloof keeps five horses in gainful employment to work the land, and has one of the most impressive composting operations I’ve ever seen. Compost is central to biodynamics, with many of the infamous preparations requiring the various outputs of animals and vegetation. Here though, the composting is done with JCBs and diggers rather than wheelbarrows or spades.

The wines are excellent, if stylistically quite mainstream. Circle of Life White 2013 is a silky blend of Sauvignon, Chenin and Chardonnay, while its red cousin (2012) has plummy, chocolate-tinged fruit and well integrated oak. The questionably named “Seriously cool” Cinsault 2015 (designed to be drunk fresh from the fridge) feels a tad too heavy on the oak for its light spicy fruit frame.

After a tasting and lunch, Nadia hurriedly makes her excuses and leaves – and the mystery of the glamorous apparel becomes apparent: She’s headed straight to a birthday celebration in Cape Town, and has very kindly squeezed in my Saturday morning appointment without missing a beat.

Avondale

Waterkloof isn’t alone in the Cape when it comes to demonstrating biodynamics at scale. Jonathan Grieve is the mastermind behind Avondale, a family estate near Paarl. One quarter of the 300 ha (740 acre) estate is under vine. Farming follows biodynamic principles, although certification is “merely” EU & USDA organic – as Grieve explains, it would cost a minimum of €4,000 extra a year to add Demeter certification, plus 1.5% of the estate’s profit.

Grieve has come up with a sort of “biodynamics+” methodology which he calls “Biologic”. The concept mixes the aims, ethics and methods of Rudolf Steiner’s teachings with rigorous soil analysis, using the Albrecht system to gain scientific insights into what is needed to improve the soil quality.

Grieve comes across as thoughtful, if not slightly reserved, with an art school background and a clear passion for his vineyards. He explains how the estate’s very poor, chemically ransacked soils were gradually coaxed back to life, by analysing the plant varieties that proliferated and cross-referencing them with their attendant soil deficiencies. He’s scathing about more industrial methods of farming: “the bankruptcy of herbicide is that the seeds [of the weeds] are still there, they can stay dormant for 30 or 40 years unless you keep on spraying. We see the soil as a pantry – if the pantry’s empty, you’re not going to be able to cook anything. So we need to restock the pantry”. That means biodynamic preparations, a wide range of cover crops (Bitter lupin, fava beans and clover are some favourites) and the encouragement of natural predators.

Animals play an important part on the estate, as demonstrated by the rather lovable duck mobile. I had previously seen ducks in action at Miha Batic‘s vineyard in western Slovenia, and here at Avondale they perform the same function – pecking off small snails that can damage the vines. Chickens also roam part of the estate, housed in a reconditioned old truck christened the “hen mobile”.

Avondale’s wines are ambitious on every level, with prices that seem high for the local market, but a relative bargain for international customers. My top picks were Anima 2014, a complex and refined Chenin Blanc packed with exotic fruit, and La Luna 2009 – a Bordeaux blend with gorgeously fresh, lithe cassis fruit.

Although Avondale and Waterkloof are different in their approach and target market, they share a focused and successful business approach. Biodynamics is an intrinsic part of the proposition, not a marketing term or a token measure that’s being trialled on a spare hectare or two. Yet this doesn’t mean there’s anything particularly esoteric or non-conformist about these wineries. They are a great advertisement for a farming philosophy which puts the elemental building blocks of any quality wine – soil & environment – first.

Why then is biodynamics so often ridiculed or pooh-poohed? Perhaps those doing the mudslinging simply don’t possess the guts or the commitment – criticism is a lot easier than practice.