Turkish wines are historic, interesting and in many cases pretty good. And the Islamic ruling party would be happy for you to take more of them away from the country.

Turkey is a fascinating place for wine researchers because it appears to be the birthplace of wine. The center of genetic diversity for wild grapes is a swath of eastern Turkey and western Armenia, and it appears that wine grapes were first domesticated there. There are about 400 indigenous Turkish grape varieties, but most are currently used for eating or as raisins. About 30 indigenous grapes are made into wine, along with international varieties that are more popular right now in the domestic Turkish market.

Tough Conditions

But while it’s buzzing with the recent approval of European MWs, the Turkish wine scene is full of landmines, mostly figurative. It’s the world’s most secular Muslim country, but in a historical irony, wine quality is beginning to flower just as the government gets more religious.

Taxes are punishing: nearly 50% on alcohol production, and another 18% VAT. Wine is somewhat fashionable in Istanbul, where the economy’s growth puts the EU to shame, but prices are shocking. Australian bottom-shelf wines sell for the equivalent of $75 on wine lists; local wines aren’t significantly cheaper.

Currently a small percentage of wines are exported, but a few different winery representatives said that government officials have let them know that if more wines are exported, various legal requirements—in a country with opaque and powerful bureaucracy—could get easier.

The best terroir might be in the eastern part of the country, a wild place where most everyone has a gun, smuggling is rampant, independence-seeking Kurds pull off occasional terrorist acts, and Muslim women in head scarfs do all the grape picking (and seemingly most of the other work as well.) Wineries often have to buy grapes through a middleman who signs a pledge that he will not use the fruit to make alcohol.

It’s difficult and even a little dangerous for winemakers to try to get growers to improve their viticulture. Until 2003 the government held a monopoly on production of raki, the anise spirit that most Turks prefer to wine*, and also owned the largest winery. So the government bought all grapes from every grower as a social benefit.

Raki producers still buy grapes in just about any condition—rotting, dried into raisins, whatever. But they pay significantly less than wineries, which led to riots when the private investors who bought the state-run winery in 2003 cut production by 75%.

“The army came to the winery to take me away for my protection,” said Daniel O’Donnell, consulting winemaker for Kayra, which emerged from the state-run company. “There were 300 people with guns outside and I was the guy who didn’t buy their grapes.”

O’Donnell drove a few wine journalists to the first vineyard in the country to be listed in a single-vineyard wine. Along the way we passed vineyards that he differentiated as “rustic” and “feral;” the ones that are merely “rustic” might have some means for getting the grape bunches off the ground, whereas the “feral” ones are what you might get if you threw some wild grape seeds around on a plot of land and went away for 50 years.

“Goats wander in the vineyard,” O’Donnell says. “Grapes trail on the ground. It’s a wonder that the wines are even drinkable.”

Five years ago, even drinkability wasn’t expected. O’Donnell talked of going to an Istanbul wine shop with British critics Oz Clarke and Charles Metcalfe and buying bottles at random. “We tasted every kind of flaw you’ve heard of, and some we hadn’t heard of,” Metcalfe said. “And Oz drank them anyway,” O’Donnell added.

Old is New Again

Today, competence and hygiene are expected. And while there are plenty of over-oaked wines from international grapes made for the domestic market, some of the best Turkish wines bring what could be called the thrill of the new, except that the indigenous varieties might be thousands of years old.

If Americans could pronounce it, I think they would embrace Öküzgözü, a cheerful, fruit-forward wine that reminds me of Zinfandel. So say it with me: O–kooz–go–zoo. It’s grown all over central Turkey. The berries are big and juicy, and it does equal duty as an eating grape, just as Zinfandel did in the 1800s. I tasted good versions from Kavaklidere, the country’s largest winery, and Yazgan, which has a French winemaker, Antoine Bastide D’Izard.

The lightest of the main red grapes in Kalecik Karasi, which is somewhat Gamay-like. A little gamey and spicy, it has the potential to become expressive and elegant in red wines like one I had from Vinkara, one of my favorite wineries. It also makes an excellent rosé. Kayra makes two rosés from it, and one very delicate wine Kayra calls “white rose” was so versatile that I found myself emptying multiple glasses of it at more than one meal.

The third main red grape is Boğaskere, and it’s a beast. O’Donnell froze some freshly harvested Boğaskere grapes so we could taste it as he does. The juice is fruity and nice; the skins are leathery, thick as a slice of pita bread and leave your mouth feeling like it has been vacuumed.

Managing the fierce tannins is the key to turning Boğaskere from punishment into pleasure. It doesn’t help that the grape comes from the wilder eastern part of the country, where O’Donnell had to have an armed guard accompany him to visit growers for his first few years.

“You tell them that if they do something, their grapes will be better, and they just laugh at you,” O’Donnell says. “I’m just some guy. They learned how to grow grapes from their grandfather, who learned from his grandfather.”

Plus, he’s still figuring out that dealing with Boğaskere requires some counter-intuitive measures, like trying to get the berries big and juicy as opposed to the normal desire for small and concentrated.

But when Boğaskere is good, it’s memorable. Kayra’s 2009 version was too oaky; its 2010 was one of the best red wines I had in the country, rich and firm, concentrated but nuanced.

And I tasted an Kavaklidere Öküzgözü-Boğaskere blend from 1994 that had aged beautifully, showing that those tremendous tannins might actually be a long-term asset if anyone decides to put some Turkish wines in their cellar.

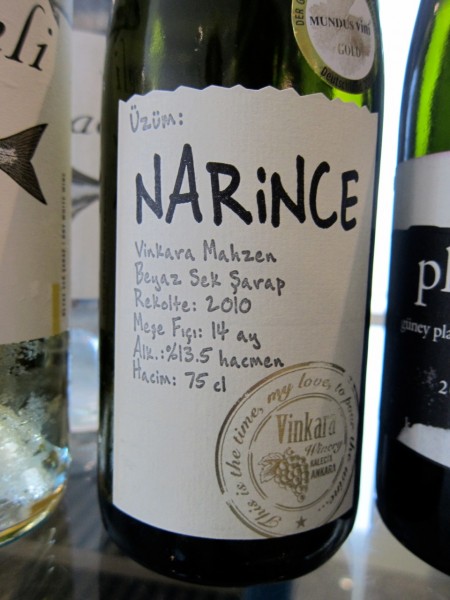

For whites, the best variety is Narince, often blended with Chardonnay. It’s actually fairly similar in texture to Chardonnay with more of an orange-blossom character. Vinkara makes an excellent version, as does the tiny winery Chamlija.

Emir is a sandy, salty, high-acid grape that could be compared with Albarino. Yazgan makes a good one, and also makes a nice blend of it with Sultaniye, which is the same as Thompson seedless.

But with dozens more grape varieties in small plantings, who knows what the future holds.

O’Donnell poured us the first taste for outsiders of a wine made from a grape called Köse Tevek. He found it growing in the vineyard owned by Sukru Baran, a Communist who spent time in prison for opposing the government before becoming a successful businessman. Baran, the first grower to really cooperate with O’Donnell, grew a plot of Köse Tevek because O’Donnell liked the taste of the grape. Maybe it’s a 3000-year-old grape; maybe it’s a recent mutation; only genetic testing could tell.

The tank sample drawn from the first vintage (2010) is delightful: elegant, smooth tannins, good fruit, a little spice. It could be Turkey’s past and Turkey’s future. If the government continues to grudgingly approve.

* The Koran specifically mentions wine. But raki—about 45% alcohol distilled from grapes—hadn’t been invented in Mohammed’s era. So there are plenty of conservative Muslims who consider wine evil, but toss back a bottle of raki a night.[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/blake2.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Wine writer W. Blake Gray is Chairman of the Electoral College of the Vintners Hall of Fame. Previously wine writer/editor for the San Francisco Chronicle, he has contributed articles on wine and sake to the Los Angeles Times, Food & Wine, Wine & Spirits, Wine Review Online, and a variety of other publications. He travels frequently to wine regions and enjoys coming home to San Francisco.[/author_info] [/author]