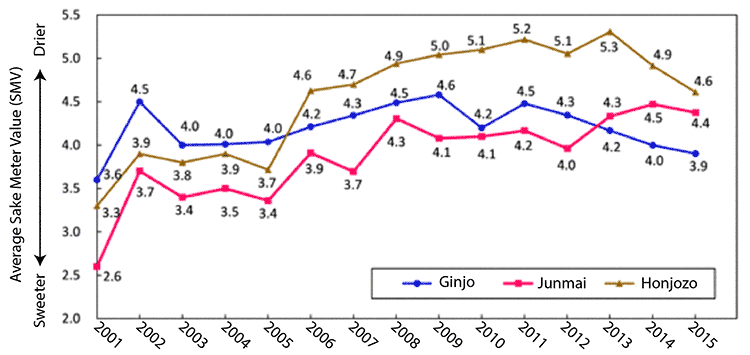

Sake is changing. The most expensive Japanese versions, Ginjo and Daiginjo, are getting sweeter on average. Yet mid-range artisanal sake (Junmai) is getting drier. As such, it may be time for dry wine lovers to give up on Daiginjo, save some money, and switch to Junmai.

I don’t believe anyone has previously reported these trends in English, but statistical proof exists from Japan’s National Tax Agency: please see the chart below. So this story is a fairly big deal. Imagine if, say, rosé was getting sweeter and Chardonnay was getting drier, and this could be proven with numbers.

I first thought breweries were making Ginjo and Daiginjo sweeter for marketing reasons, but that’s only partially true. I’ll get into why this is happening in a moment.

I discovered these trends the old-fashioned way: by tasting, as a judge at the 16th U.S. National Sake Appraisal in Honolulu. Unlike appraisals held in Japan, which attract experimental sake made only for the competition, the Hawaii event is open only to commercially available products. We tasted 381 in two days: 375 from all over Japan and six from the U.S.

To the credit of competition organizers, they tested each entry for glucose level and arranged our blind tastings in that order, driest to sweetest. Though the averages shown above don’t necessarily mean anything about individual bottles — there is dry-ish Daiginjo and sweet-ish Junmai — by the end of the Daiginjo round, my mouth felt so full of sugar that I could barely tell them apart. Though I first I blamed myself, after asking around I discovered that it was not me, sweet Daiginjo, it was you.

Before we delve further, let’s define a few things:

- Ginjo and Daiginjo are classified by the amount of each rice grain that remains after the outside is polished away (60% for Ginjo; 50% for Daiginjo). The polishing ratios on bottles are what’s left of the rice, not what was taken away, so a sake with 33% had 2/3 of the rice polished away. This process removes impurities, and while some polishing certainly improves sake, at some point one person’s impurity might become another’s flavor element.

- Junmai is defined as “pure rice,” meaning no brewer’s alcohol is added. Most (not all) Ginjos and Daiginjos are also junmai. Here’s the important part — a sake that is classified as Junmai and NOT Ginjo has a polishing ratio no higher than 70% (meaning 30% polished away). When sake people, including me, talk about Junmai, this is what we’re talking about: the category that is not Ginjo. A good restaurant sake list will divide bottles into Daiginjo, Ginjo, Junmai and maybe Futsu-shu (ordinary), Nigori (the cloudy White Zinfandel of sake) and Honjozo, an aficionado’s category I won’t get into here.

- Sake is one area where, unless one resides in Japan, locavorism doesn’t apply. Japanese sake is still significantly better than those from any other country. None of the six Americans entered in the event won even a silver medal, and I don’t know if U.S. sake makers will ever catch up to the Japanese; it’s a bigger quality gap than with any kind of wine or spirit.

Now, let’s unpack those sweetness and dryness trends.

First, about Ginjo and Daiginjo getting sweeter.

It appears that yeasts are a culprit — yeasts, and the influence of wine on sake drinkers.

Sake is higher in alcohol on average than wine: about 18 to 20% at cask strength, or about 15-16% at bottling. Traditionally, brewers chose yeasts that could ferment all the sugar. Most native-yeast sake is dry or nearly so; the yeasts have adapted.

As in the wine industry, cultured yeast is a big part of sake now. One reason brewers like it is that it’s possible to use yeasts that create aromatic compounds. Though twenty years ago aromatic sakes were relatively rare, their recent popularity has caused proliferation.

“Yeasts that create the most aroma don’t completely ferment the sugar,” explains Ryuichi Yoshida, president of the brewery that makes Tedorigawa, dry sake with a saltiness that reflect their seaside Ishikawa prefecture region. (So if that sounds like a good wine, check them out.)

Yukio Hamada, director of the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers’ Association, adds that yeasts that deliver aromatic sake also create caproic acid, a compound also found in butter and beer that tastes bitter.

“The technique to cover the bitterness is to leave more sugar,” Hamada tells me.

Second, about Junmai getting drier.

Dr. Hirata Dai, director of research and development at Asahi-Shuzo brewery in Niigata prefecture, thinks the fact that these sakes are getting polished more is a factor. In other words, the increase in starch content and decrease in other stuff from the grain’s outer layers has helped lead to more efficient fermentation.

Of course, if a Junmai was polished a little more, it would be a Ginjo. So this gets back to yeast and a marketing decision. It’s not about sweetness: it’s about aroma. Sake drinkers expect Ginjo and especially Daiginjo to smell floral and fruity, but they do not expect the same of Junmai. As a result, the latter is becoming more pure than ever, and that includes dryness.

Over the years I’ve noticed that people who drink a lot of sake professionally — importers, sake sommeliers, knowledgeable chefs — tend to praise Junmai. It’s not flashy like Daiginjo, nor is it aromatic. It is often boozier, and the taste of rice itself is more common. But now I understand this. Tasting blind, I absolutely loved certain Ginjos: three of my five favorite were labelled as such. None of my very favorites were Daiginjo, a bit of an upset because those are the most expensive, but partly that can be explained by palate fatigue.

As a group, however, I most enjoyed tasting the Junmai. They had slightly higher acid on the whole, while many had that saltiness that I like. The ceiling perhaps wasn’t as high as with Ginjo, but the floor was much higher: I would drink the worst of the Junmai.

That’s true to a certain extent of Japanese sake in general; there was really no version — out of 375 — that actually tasted bad, something that’s never true in wine or spirits competitions. I thus feel comfortable concluding that it is still one of the world’s greatest beverages and beverage values, even as it gets sweeter — or drier.