This should be a success story.

In 1990, Fukushima prefecture got zero gold medals at the Japan sake awards. This was just when Japanese consumers started to pay more for premium sake, so the local government took the embarrassing shutout seriously.

Fukushima’s government started a sake academy to teach brewers to make better ginjo sake. (At least 40% of the rice grains are milled away for “ginjo”; for “daiginjo” it’s 50%.) Scientist Kenji Suzuki created a “ginjo manual” for the region’s breweries, re-engineering the clean, aromatic, long-finish profile that the national judges like. It wasn’t anywhere near as simple as “grow good rice.”

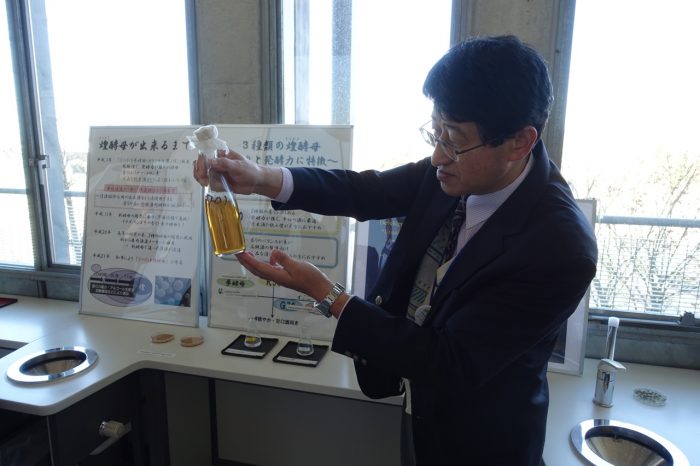

Suzuki isolated two aromatic yeasts and recommended that everyone use them. He recommended a particular strain of koji mold for transforming rice starch into sugar, and an ideal temperature for the mashed rice at a crucial phase. He developed a Fukushima strain of rice, Yume no kaori (“dream fragrance”) by crossing strains from Yamagata to the north and Hiroshima to the east.

In essence, Suzuki created a regional flavor, something like what Cistercian monks did in Burgundy when they settled on Pinot Noir for red wines. But the monks needed generations. Suzuki realized success in just 16 years.

By 2006, Fukushima won 23 gold medals at the same competition, the most of any prefecture in the country. Fukushima has since won the most gold medals five more times, including the last four years in a row.

Success! But there’s one rather enormous problem. Consumers are now wary of Fukushima sakes, not because of their quality, which is impeccable, but because of the nuclear reactor meltdowns of 2011 that released radioactive material into the atmosphere.

In the immediate aftermath of the meltdowns and the devastating tsunami that caused them, Japanese consumers came to the support of local farmers.

“Right after the tsunami, the governor of Tokyo said it was a time of mourning and people shouldn’t celebrate cherry-blossom viewing,” said Inokichi Shinjo, chairman of the Fukushima Sake Brewers’ Association. “But a brewer from (neighboring) Iwate (prefecture) did a Youtube video where he told people that if they wanted to support the region, they should buy sake. People rushed out to buy sake and brewers from Tochigi and Iwate sold out. But by the harvest of 2011, people started to worry about radiation. A grocery store in Tokyo said it would only sell Fukushima sake if it is tested for radiation.”

Fukushima prefectural officials tried showing on maps how most sake comes from the west of the prefecture, separated by mountains from the nuclear plants to the east. How wind patterns kept radioactive materials away from the rice paddies. They became experts on the language of radiation: how many becquerels are considered safe in drinking water in the European Union, or the US. Which types of radioactive materials reach half-life fastest. They could, and did, talk your ear off about why their sakes are safe.

Still sake sales slumped. So they set up an extremely expensive program. Every bag of rice in Fukushima prefecture, either for consumption or for making sake, is now tested for radiation. Every one. Every bag of rice has a unique bar code and anyone can look up the radiation results online. The testing is paid for by the prefecture, which gets compensation money from Tepco, owner of the nuclear plants. None of the neighboring prefectures do this, and some were at greater risk of contamination. But in Japan, the name Fukushima, for a generation at least, will always conjure images of first the horrific tsunami and then the nuclear meltdowns. To replace those with the image of delicious sake will take some doing.

What I found, in visiting Fukushima last year, was sake that ranged from good to superb. It’s easy to focus on the most expensive, most delicate sakes. What impressed me most were some of the cheapest. At dinner one night, we had a 180 ml bottle of nama (unpasteurized) sake from Suehiro that cost 400 yen (about $4 US). It sat on the table with, and emptied just as fast as, the highest-end sakes from three other brewers. Shinjo, who is also president of Suehiro, said he makes the sake from government-grown rice and hasn’t raised the price in 30 years. A generation ago it was a splurge, I suppose, but now it’s one of the best values you’ll find.

But even before the tsunami, Fukushima determined its path to be excelling at higher-end ginjo and daiginjo sakes. Japanese consumers don’t drink as much sake as they did in the 1980s, so volume sales aren’t as good a path to financial success as making expensive brews. And the string of gold medals shows that Fukushima does these as well as anyone.

Daishichi Masakura Junmai Ginjo was one of the best sakes I had last year, with lively peach character and satisfying richness. Daishichi breaks the Fukushima formula by using only the ancient kimoto method, and relying on native yeast, to make its sakes. “We get such strong deep flavors because only the strongest yeast will survive being in the environment with the other microbes,” said Daishichi president Hideharu Ota.

In contrast, Niida Honke followed the formula with its Shizenshu Junmai Ginjo to win a gold not only domestically, but in the sake category at the International Wine Challenge. But I preferred the brewery’s less expensive Bangai Kimoto Junmai Ginjo for its fresh melon and citrus peel flavors. Unusually for Japan, Niida Honke uses only organic rice. “We don’t actually ask local farmers to grow organic,” 18th generation brewer Yasuhiko Niida said. “Instead, they come to us.”

Perhaps the best story from Fukushima is from Tsuru no E, a small brewery now run by the unusual team of brewmaster Yuri Hayashi and her husband Yoshimasa Sakai. Female brewers are still rare in Japan, but it was Hayashi’s family’s company.

Hayashi and Sakai met in college in Tokyo, where they studied brewing. Sakai, who went to work for a human resources company after graduating, said he chose that major because “I liked to drink sake. I didn’t want to study business or the economy or politics.” He said, “We weren’t dating at college. We were just classmates. Then I came to work here. I realized we were always fighting.” So naturally they decided to get married. Their sakes are clean, fruity and pretty: the taste of Fukushima.