Have you met Brett? Brett is mentioned so often in the wine industry that you might think he’s Robert Parker’s protégé nephew. Not so, but the truth is just as controversial.

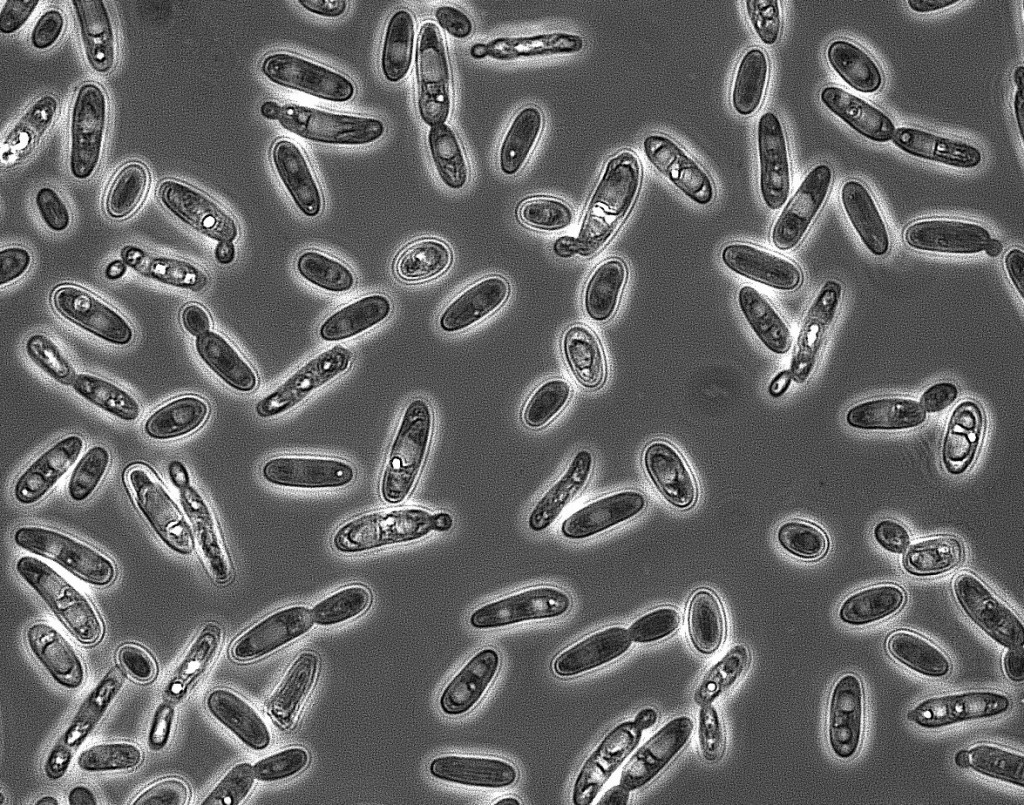

Brett, known technically as Brettanomyces bruxellensis, is a yeast. That puts it into the same category as our old friend Saccharomyces cerevisiae, used for millennia to ferment juice into wine, and make bread rise.

Brettanomyces can ferment, too. It was first discovered in beer (as a cause of spoilage in an English ale, hence the name which means “British fungus”) and is used to advantage by some adventurous brewers in sour ales.

In wine, though, Brett is never added on purpose, but often finds its way in by accident. The “stealth bug” of the wine microbial crowd, Brett grows very slowly and can survive on remarkably slim pickings: the tiny amount of sugar found in “dry” wines, ethanol (yes, it can use alcohol as an energy source), acetic acid, and even the cellulose in wood.

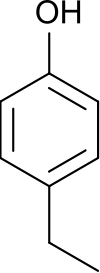

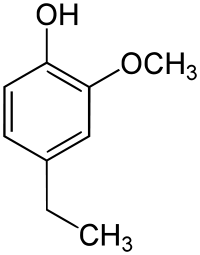

If you’ve ever tried sour ale, you have an inkling of the flavors associated with Brett. One of those flavors, naturally, is sour: Brett can produce gobs of acetic acid, the same acid that gives vinegar its tang. Long before it tries to turn wine into vinegar, however, Brett throws off troublesome smelly compounds that clearly mark its presence: 4-ethylphenol (4-EP), 4-ethylguaicaol (4-EG), and isovaleric acid, among a few less notable others. “Unique” is the nicest way to describe these aromas. At best, you might call them “spicy” and “leather;” at higher concentrations, “barnyard” and “horsey;” at worst, “wet dog” and even “sewage.”

Spice and even occasionally leather can be appealing in some wines, but horsey or sewage odors are certainly not a compliment. Whether Brett character in a wine is good, bad, or acceptable is like the debate over what constitutes “real” barbeque among Southerners: the argument is a matter of subjectivity and taste, meaning no one can ever win.

Historically, the French Rhône Valley has been associated with reds containing Brett. Some prominent houses—Château de Beaucastel perhaps most famously—are so well known for a certain degree of Brett influence that it defines part of the house style. The key words there are “a certain degree.” Admirers say that a little bit of Brett–the spicy rather than the sewage end of the spectrum–contributes to an earthy texture and accentuates terroir. Others—notably most Americans—claim the exact opposite, that Brett destroys both fruit and character.

So what if you do want a some of these characteristics in your wine? Could you just throw a little in?

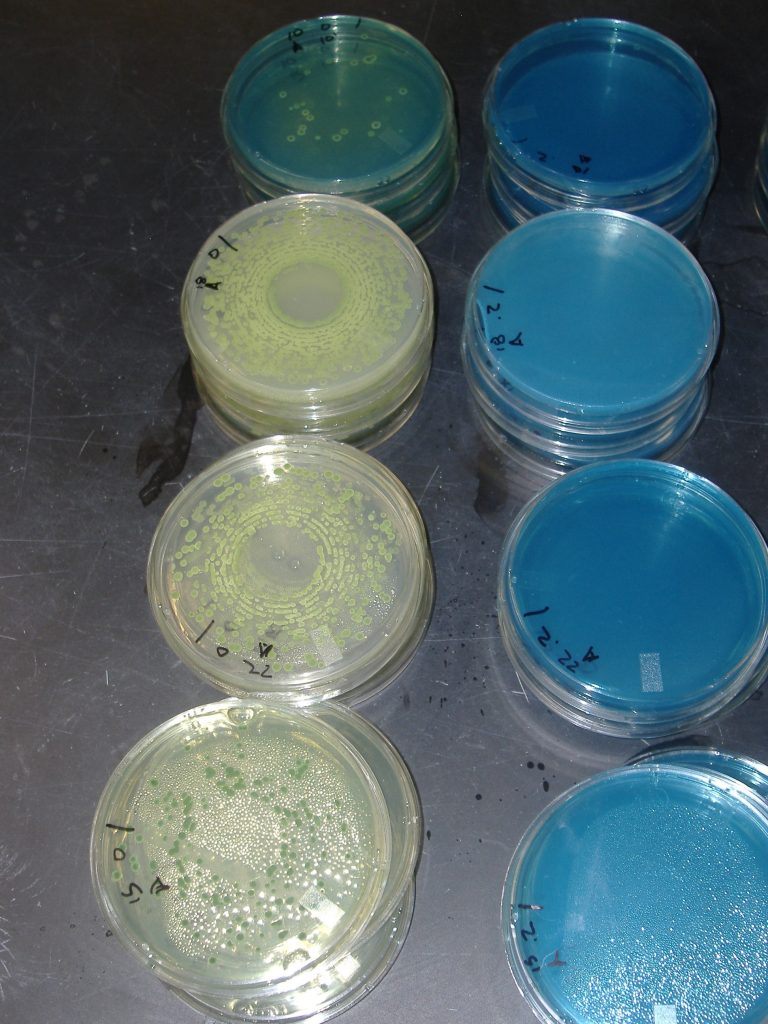

If only it were that simple; winemakers would rest a good deal easier at night. In truth, the struggle to bridle Brett has gone on for decades and is as yet unsuccessful. Not only can we not yet control the amount of Brett in a wine, we can’t even completely eradicate it. A popular suggestion for how to deal with a Brett problem is “burn down the winery and start over.” The speaker isn’t always joking.

How does Brett infiltrate a winery? Another million-dollar question. A few theories dominate the discussion, but it remains a contentious debate. Brett can move from winery to winery in contaminated wine (bulk wine sold from one winery to another), on grapes, or on used equipment.

Used oak barrels are notorious carriers of Brett. With its unusual capacity to metabolize the cellulose in wood, the microorganism can survive in oak barrels for years. Brett has been found as far as 8mm deep into the oak, making decontamination nearly impossible.

If burning down the winery and starting over again isn’t an option, what is? One tactic is to keep the infection localized to a few barrels, blend, and decide that you like some Bretty-ness in your wine. Alternately, bring out every antimicrobial agent in the book, cross your fingers, and pray.

The anti-Brett arsenal is vast and continually growing but, as a whole, not all that potent. The most common and most effective solutions include:

- Good winery hygiene: Lots of water and sanitizing solution go a long way.

- SO2: Sulfur dioxide is used as a general antimicrobial agent in wine, but many Brett strains are resistant to the legal maximum dose.

- Hot steam sterilization of barrels: Expensive and not completely effective, but helpful.

- Velcorin: A powerful antimicrobial chemical (trademarked by Scott Labs) that breaks down to (mostly) water and CO2 only a few hours after being added to wine and, like everything else, is only partially effective against Brett.

- Filtering: This will do the job, but at what expense? To some, the only cost is the time and money spent on filtering. But some believe the 0.45 – 0.65 micrometer membrane sterile filtration necessary to eliminate yeasts also eliminates spirit and identity.

Some wineries don’t seem to have contracted Brett (yet), some wage constant war against the microbial monster, and some don’t acknowledge it.

Some wineries don’t seem to have contracted Brett (yet), some wage constant war against the microbial monster, and some don’t acknowledge it.

But what about wineries—like Château Beaucastel—whose shade of Brett character is downright alluring, at least to some connoisseurs? For them, total Brettanomyces extermination might prove disastrous. What makes a little a boon to some wineries and a bane to others? Is it all personal taste, or are other factors involved?

People who become very excited over Brettanomyces are investigating those questions at this very moment. Just a few of the possibilities include:

- Consumer preference: Some published research suggests the French tolerate more Brett character than Americans.

- Amount of 4-EP and 4-EG: Some wines naturally have less of the precursor molecules that Brett metabolizes to 4-EP and 4-EG. In general, grapes from cooler climates—like France—have less of these compounds than grapes from warmer climates, like parts of California. That might mean French wines start off less likely to become stinky when Brett moves in than their Californian counterparts.

- Ratio of 4-EP to 4-EG: 4-EP is usually associated with unpleasant barnyard aromas, while 4-EG aligns with far more pleasant clove and spice notes. 4-EP always predominates over 4-EG, but some strains of Brett, and some wines, are predisposed toward higher ratios than others.

- Type of Brett: What if the Brett strains found in different places have different characteristics? It is often true in microbiology that great variability exists among strains (different organisms isolated from different places) within the same species. Research is beginning to show that the Brett lurking in French wineries may have radically different characteristics than that in California or Australia.

- Age of the wine: Not only can Brett survive locked up in a wine bottle, it can multiply and yield its signature aromas. The wine you find seductively barnyardy today may reek of old horse sweat in a few years. Even a single cell per bottle can make a difference, as fans of filtration love to point out.

So, have you met Brett? Even though you may not have realized it at the time, the chances are excellent that you have sniffed Brett’s signature scent sometime in your life with wine.

Perhaps you would like to revisit the experience with greater awareness? Don’t look for “hint of Brettanomyces” on the back of a wine label; to most winemakers, that idea is worse than cursing the family name.

Perhaps you would like to revisit the experience with greater awareness? Don’t look for “hint of Brettanomyces” on the back of a wine label; to most winemakers, that idea is worse than cursing the family name.

No guarantees, but the best-stocked Brett fishing holes are barrel-aged reds from the Rhône valley, Rioja, Piedmont or Chianti, and perhaps Bordeaux. Brett can certainly be found elsewhere, but your odds become less certain. Explore.

Do you fall among the hard-line anti-Brett crowd, or among those who enjoy a little Brett in the right place and time? If you have not already leapt to your feet to lobby for one side or the other (did I mention people tend to be a bit vehement about Brett?), begin paying attention. Keep your eyes, mouth, and nose open, and consider that a particularly distinctive aroma may be Brett’s calling card. Most importantly, form your own educated opinion.