Sometimes a wine is so good, so special, that it stays in your brain for days. Weeks, or even months. And sometimes it can force you to confront what you think you know about wine.

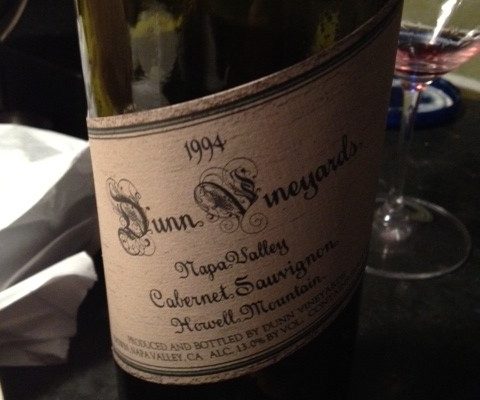

That was the case after I was mesmerized by a bottle of 1994 Dunn Howell Mountain Cabernet. It wasn’t just that the wine was excellent—it was—but that the wine seemed to come from an entirely new place. If I stretched my memory, perhaps it evoked older Mayacamas wines, but not much else. And it seemed built for only the most gradual, riveting evolution.

Why, then, is the current edition of this wine only $75 a bottle? Why isn’t it a cult wine with a vertiginous price scale accessible only to those who know the secret handshake?

A friend remarked of that ’94 Dunn, “That’s a mountain-fruit wine. Those wines age much better than wines from the valley floor.”

It’s never quite that simple when it comes to wine, but I wondered if he were on to something. There is a large segment of the wine-buying population that wants high-end Napa Cabernet. And who better to ask about this, I thought, than Randy Dunn himself. Turns out that Dunn is not only convinced that mountain fruit is superior; he’s concerned that thousands of wine buyers are getting the kind of advice from major reviewers that will lead them to waste hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars.

“There’s definitely a difference”

It’s wise not to over-generalize when talking about wine. But Randy Dunn doesn’t mind saying that mountain Cabernets age better than their counterparts from the valley floor. “That’s a fair generalization,” Dunn tells me during a short break on a harvest day. “The wines with the best track record tend to be mountain wines.

On a recent trip to Mayacamas, a mountain property that sits high above the valley floor, I noticed that the berries looked smaller. Dunn says mountain grapes grow to be smaller, tighter. Mountain winemakers say this leads to more intensity, more structure, less of the monolithic richness. But here, Dunn warns that not all mountain Cabernets are the same: “We can get it raisiny up here, too. Many of us just choose not to.”

That means wines with lower alcohol levels and more tannin. According to Dunn, those are the most important ingredients for Napa Cabs that can improve over many years in the bottle. Here’s an excellent piece that details some of what separates mountain fruit from valley floor fruit. (LINK)

But I asked Dunn: Isn’t it possible for valley floor producers to make similar wines? “We were doing that at Caymus in the old days,” he says with a laugh. “Things have changed. That’s all I can say about that.” I press him: Is anyone making ageworthy wine on the valley floor today? “Cathy Corison,” he says. “She’s the only one that comes to mind right now.” Dunn pauses, then shouts to someone in his winery. “Who’s making low-alcohol wines in the valley?” Another pause, then, “Yeah, Corison. That’s about it.”

I don’t necessarily agree with Dunn’s assessment; Araujo and Dominus, for example, are making long-lasting wines of distinction. But I agree that mountain wines are more likely to last a long time—and improve with that time in the bottle. There’s something else bothering Dunn. He says consumers are spending huge amounts of money on wines with gaudy point scores, but many of those wines will be dead by the time they’re uncorked.

“They’re absolutely getting screwed”

Dunn is not a fan of modern Napa cult wines. “They pop up overnight and command top dollar,” Dunn says, “but what do we know about them? People follow the points. I had hoped that things would have changed by now. They haven’t. It’s so obvious that it stinks.”

Then he laughs again: “These reviewers want all Napa wines to taste the same, and you know what? They all do. Good for them.” (Dunn is less caustic when talking about Wine Advocate’s Antonio Galloni, who has recently offered praise for Dunn wines.)

The result of this obsession with high-alcohol, high-scoring wines, Dunn says, is going to be a lot of anger on the part of consumers. He predicts wine buyers will be furious when they open some of these wines in 20 years. “They’re absolutely getting screwed. They buy these wines and they’re told to hang onto them. Most won’t last. That’s a lot of money going to waste.”

His solution is to look for wines with lower alcohol, for starters, but there is another pitfall in that game. Legally, wines that are higher than 14% alcohol by volume can be labeled one degree higher or lower than the actual amount. Some random tests have shown that these wines tend to have more alcohol than the imply indicates. “If you were a gambler,” Dunn says, “and you wanted to bet, you could get rich betting that everything above 14 alcohol is, on average, actually point-nine higher than listed. You’d win. Much, much more often than you’d lose.”

I went back and checked the label of that ’94 Dunn Howell Mountain: 13%.

Another viewpoint

For some perspective I turned to a man with a great cellar, and a man who has done some of the finest writing about California wine for decades: Charlie Olken, publisher of the Connoisseur’s Guide to California Wine.

“There are plenty of examples of hillside wines that age quite well,” Olken agrees. “Ridge is the most obvious example, and it is followed closely by Diamond Creek, Chappellet, Pride and plenty of others.”

But Olken disagrees that the valley floor wineries have passed the point of making ageworthy wines. “Regardless of what Randy says, he is so set in his belief that alcohol is a determinant that I think he misses the point,” Olken says. “The wines of today are not all that much changed. One percent alcohol has not destroyed them.” (Keep in mind that Dunn is arguing that many wines labeled as one percent higher in alcohol are probably closer to two percent higher.)

Olken offers some valuable historical insight. “Fruit bomb” might have been Robert Parker’s neologism back in the 1980s, but French winemakers were accusing California of overly ripe, drink-now wines back in the 70s. Olken explains, “When California wines did so well in the 1976 Paris tasting, the French and their fans tried to dismiss the results as California (having) early drinkability, and thus they argued that the French wines would be better, more complex in two decades.” This hasn’t necessarily unfolded as predicted. “A number of re-tastings have been conducted by various groups as the wines aged, but with inconsistent results as to which wines aged better…There was never any reason to doubt the performance of the flatland California wines in those tastings.”

Dunn isn’t surprised that his views aren’t widely accepted. “People think I’m a fanatic,” he says. “An extremist. But the proof is in the wines.” Of that 1994 Howell Mountain that I so enjoyed, Dunn tells me, “It’s coming around. It’s pretty good. They’re just now getting there, the wines from the 90s.” It would be remarkably egotistical hyperbole if it weren’t true, based on recent tastings.

Changing the meaning of “cult wine”

If Dunn is right, and countless high-end Cabernets from the floor of Napa Valley are going to be fat, soupy messes in a decade, then the question becomes: Will winemakers change their habits? Dunn feels that instead of the valley floor following the mountain’s lead in recent years, more mountain producers have decided to make high-alcohol wines. He’s quick to name names, which might upset his neighbors, but Dunn values honesty before tact. He points to Ladera and Lamborn in particular.

With just a whiff of optimism, Dunn says, “Maybe last year will shake it up.”

2011 brought a very challenging vintage for Napa winemakers, and Dunn points out, “They couldn’t get the wines as ripe as they want. Fewer people were cranking them up. Maybe they’ll learn something.” Like what, I ask? “Maybe they’ll learn that lower-alcohol wines are better wines.”

But then Dunn laughs and adds, “They’ll probably just learn that reviewers give low scores to wines like that. And they’ll go right back to what they were doing.”

He might be right. It won’t be long before we can decide whether Dunn is correct in his assessment of high-end Cabernet or if he’s just a cranky winemaker up on the mountain. Schrader wines have just crossed a decade; Scarecrow, a white-hot wine, is just a few years old. There are countless others that fetch triple-digit prices but have yet to pass the toddler phase.

One thing is certain: It will be far less expensive to build a vertical of Dunn Howell Mountain Cabernets, and—with a little patience—the results are likely to be captivating. That’s the kind of wine that should build a cult following, even without the garish prices.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/evan.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Evan Dawson is a news anchor / reporter at the ABC News affiliate in Rochester, NY. He has reported on public policy and politics for more than 10 years. He is the Managing Editor of the New York Cork Report, as well as the author of the critically acclaimed Summer in a Glass: The Coming of Age of Winemaking in the Finger Lakes.[/author_info] [/author]