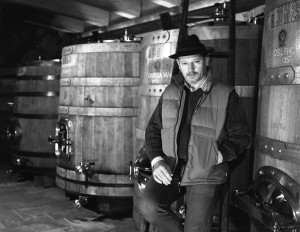

At almost two meters in height, with broad shoulders and sturdy hands, Paolo Vodopivec looks well adapted to work the land that is Carso. When I drove through this northeastern Italian region a year ago, I felt tremendous respect for the work he and other local winemakers do in an environment dominated by stone—lots of it—and Bora wind. To survive on this land, one must be resilient to nature’s challenges.

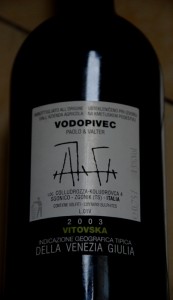

Vodopivec himself describes the region, located above the Gulf of Trieste, as harsh, unpleasant, and difficult. But Vodopivec, based in Sgonico, a small village above Trieste, seems to have tamed the wild Carso. His ten hectares comprise solely Vitovska, until recently an obscure local white variety. But in Vodopivec’s hands it produces fruity, well-balanced, and complex wines full of mineral notes—a proof that Carso, despite its wildness, has much to offer.

I recently caught up with Paolo Vodopivec, as well as with his well-respected winemaking colleagues Dario Princic and Stanko Radikon, at the Wine and Gastro Festival in Zagreb, Croatia, to talk about their production and the future of wine.

“Vitovska is a variety with lots of identity. It provides a direct connection to Carso,” Vodopivec says. “People who drink Vitovska but have never been to Carso can easily understand this region; because Vitovska is a variety that speaks Carso language, it can tell you what Carso is. It is the best business card for this region.”

He talks of his vision of Vitovska in a globalized context, where the wine serves as an ambassador of the territory, the land, and the work of the winemaker. He praises the way Carso pays him back for the effort and work he has invested. Talking about the wine industry today, Vodopivec expresses fears of the loss of identity and the standardization of the products, leaving little in the way of distinctive links to a territory, variety, or producer.

“Wine has to have a spirit, has to have an identity. However, we are witnessing a trend of massive wine production that is changing all this.” Such mass practice makes little sense to Vodopivec, who hopes for a totally different kind of future, one of honest work that helps the grape achieve its full potential. “Man should not intervene in nature or the cellar. Wine has to be the result of such a practice.”

Vodopivec’s words are very much echoed by Dario Princic, a producer from the globally better known region of Collio, the fourth largest DOC in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region in terms of area planted. Located in the village of Oslavie, just north of the town of Gorizia, and a few steps from the border with the neighboring Slovenia, Princic is a small organic producer with five hectares and 40,000 vines.

“Of course the future of wine is in natural production,” he says. His wine is hand-made, literally. No mechanization is allowed, and no added chemicals. Only natural cow fertilizers are used. “Animals eat the products of the earth. By using only natural fertilizers, we are giving back to the earth. Using chemistry is a whole other story,” he says.

Princic is no salesman, but nor is he a businessman in the classical sense. His coarse hands bear witness to the hard work he puts into the production of each bottle. Up to two and a half vines are used to produce a bottle in a very artisanal production process. “Big industry is destroying nature. It is destroying people, too. That’s why the future lies in natural production,such as ours. Once you try this type of wine, the next morning you feel as if you had milk.”

Princic’s neighbor from Oslavie, Stanko Radikon, boasts cult status among global wine buffs and is an icon to many of his fellow winemakers. Radikon proudly insists on making wine “as my grandfather used to in the 1930s.”

“The future of wine is for winemakers to take two steps backwards and for wine to move two steps ahead,” he notes, with a generous laugh.

Like Vodopivec and Princic, Radikon hand-harvests his 12 hectares, adds no yeasts, and adds little or no sulfur. His philosophy is to make a natural, organic wine with the least human intervention possible and with the maximum respect for the soil and nature. “Today, winemakers are given more significance than the wine they make. If there is no one to support wine, that’s a problem.”

Obviously a man of his native soil (and a bit of a philosopher, as well), Radikon is a big supporter of local varieties. To many in the wine community, his ribolla vineyards produce the best example anywhere of that white variety. He also grows tocai friulano. “Our reality is to respect the local varieties and to open the possibility for our soil to realize its full potential,” he says. “I think the future is bright for our kind of wines because people feel the goodness in them.”

With more passion than practically any other winemaker, Radikon speaks of wine as a part of a culture, a medicine that helps people feel better. “The chemical industry, as well as the wine industry, is so powerful that it’s endangering our philosophy. But I am an optimist. We are stubborn and I think we shall survive the attack.”

Marko Kovac is a communication and public relations consultant living in Croatia, focused on building promotional identities for companies and individuals off- and on-line. He had previously worked as a journalist and editor for national and international news outlets. With a strong passion for wines with character, made in a way that respects nature, he often travels in search of winemakers who share this philosophy. E-mail him at kovac.marko (a) gmail.com or find him on twitter @MarkoKovac

Marko Kovac is a communication and public relations consultant living in Croatia, focused on building promotional identities for companies and individuals off- and on-line. He had previously worked as a journalist and editor for national and international news outlets. With a strong passion for wines with character, made in a way that respects nature, he often travels in search of winemakers who share this philosophy. E-mail him at kovac.marko (a) gmail.com or find him on twitter @MarkoKovac