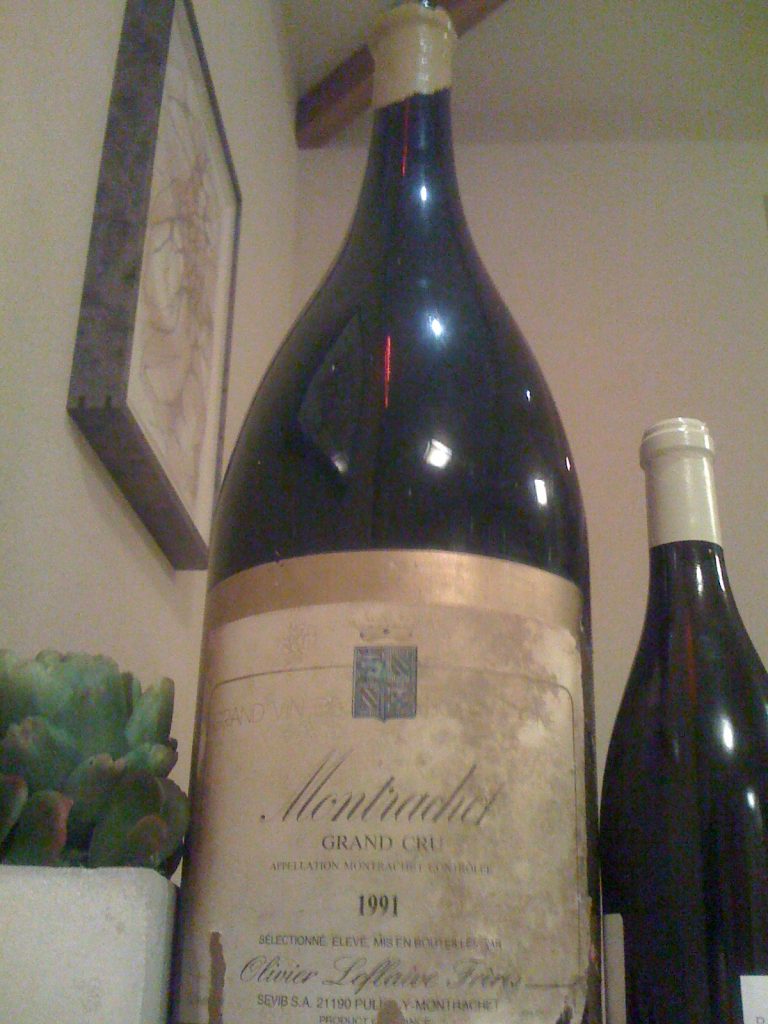

Michael Madrigale hadn’t really intended to bid on the six-liter bottle of 1991 Olivier Leflaive Montrachet, but as he looked around the room at the Acker Merrall & Condit auction, he couldn’t find a single paddle in the air. How was this possible?

The minutes trudged by, awkwardly, and Madrigale was tempted to wonder if there was something wrong with the bottle. After all, this was the “most blessed piece of land in the known universe,” he liked to say. The auction price of $650 should have been a low starting point; instead, he could feel the blood pulsing in his temples as he considered attempting to snag the bottle without a second bidder. The provenance was sound, and Leflaive was known to have produced large-format bottles. With the final seconds ticking off, one question flashed in his head, and as he tried to shake it off like migraine aura, it only grew louder:

How can I not?

Madrigale raised his paddle and picked up the steal of the auction, paying a total of $800 after the vig. He was left with only one problem. He had no idea what the hell he would do with it.

What to do now?

It was September 2009, and Madrigale had been the sommelier at Bar Boulud in Manhattan’s Upper West Side for less than a year. There didn’t seem to be a fit for the bottle in his wine program. (This was before the days of the coravin.) He couldn’t expect the bottle to move if it carried a standard markup (which would have been around $3000, at least). And if he tried to sell it by the glass, it was also sure to be a dud: even the geekiest wine lovers struggle to summon $100 for a single glass.

“I had a bit of buyer’s remorse,” Madrigale admitted.

Bar Boulud had attempted to sell wine by the glass from larger format bottles in early 2008, before Madrigale’s arrival, but the program had stagnated. Customers didn’t show enough interest to make the program a financial success, and when a large number of magnums were wasted, the program was essentially abandoned. But now, stuck with a 6L bottle that wouldn’t sell via conventional methods, Madrigale saw an opening to revive the big-bottle program.

His first goal was to make sure the entire bottle (an Imperial, technically) would sell. Madrigale is a Burgundy fanatic who couldn’t stomach the thought of Montrachet going down the drain, and he didn’t want to find himself lugging a half-finished bottle back to his apartment, just to make sure someone drank it. To ensure it would move, Madrigale decided that the price had to be lower. Much lower.

“Where have you ever gone where you were offered a bottle of Montrachet by the glass?” he said. “In a six-liter bottle, no less! I wanted to create something special and have guests come in and say, ‘Wow.'”

He did the math and figured that he could get 32 glasses. He would charge $25 a glass in order to break even on the $800 cost. He told his staff that this Imperial of Montrachet was the canary in the coal mine, and he would quickly know if there was a future for a big-bottle program. The advantage was that no one else was doing anything like it. If it worked, Bar Boulud could create something special.

Madrigale opened the Imperial on a Friday night, their busiest night of the week, hoping he could sell 16 glasses that night, and the rest on Saturday. That afternoon, he had created a Twitter account on the advice of his waiters, who explained that this new form of social media was “like sending a text message to all of your friends at once.” He took a picture of the bottle, tweeted it out, and offered the first glass at 5pm. Don Giovanni was playing at The Met across the street, and Bar Boulud was jamming by 6pm. An hour later the Montrachet was gone, and a new program had been launched.

Would you like some 1982 Monte Bello?

It was only a coincidence that my wife and I were making a visit to Bar Boulud on the night that Madrigale was opening a 5L of 1982 Ridge Monte Bello, an iconic California wine. I could hardly have come up with a more exciting wine to taste by-the-glass. Madrigale wasn’t pulling anything special for us, of course, but he was most certainly using this rare bottle as bait. Paul Draper was in Manhattan and Madrigale was hoping he’d come to the restaurant to taste his wine.

Draper is a winemaker who has recalcitrantly declined to follow the trends that have pushed California wines ever bigger, fatter, thicker, hotter. As a result, he has become a titan in the industry, beloved not only by his colleagues but by wine lovers who knew his wines were special even in the early days. None is more celebrated than the Monte Bello bottling, a Cabernet-dominated blend from the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Madrigale had met Draper before. In fact, the day before the sommelier pulled the 1982 Monte Bello, Madrigale had attended a lunch with nine other sommeliers, hosted by Draper, to taste the current releases. But Madrigale confessed to wanting more time, one-on-one, with Draper. The 1982 was the lure; he mentioned that he’d be happy to open it with Draper, for the winemaker’s inspection.

Madrigale knew this was not a typical Monte Bello, however. It checked in at 11.5 degrees alcohol, low even by older standards. Draper was hesitant; he told Madrigale that it had been a dicey vintage, and he had worked to make sure crop levels didn’t dilute the wine. He suspected it might be long past its drinking peak. Nevertheless, Draper was curious enough to come by. Madrigale had plenty of other large-format bottles he could open if the Ridge was a dud.

By the time my wife and I arrived, the peripatetic Madrigale was a blur, moving the bulky Monte Bello bottle from table to table, from bar to dining area, even next door to customers at Boulud Sud. He was smiling. He’s often smiling, but it was immediately clear that he was enjoying offering guests the chance to taste this wine.

“It’s showing okay?” I asked.

“Paul was trying to keep expectations down,” Madrigale said, still grinning, “but when we poured it for him, he was excited. He thinks the large-format has preserved it.”

No one would claim that 1982 Monte Bello was the most majestic wine they’ve tasted, but it was remarkably structured and complex. It finished a bit short, likely due to the troubled nature of the vintage, but it was otherwise a more lithe sibling of top Monte Bellos. How many bottles are still around, I wondered? How many are good enough to drink?

That is another magical component of Bar Boulud’s big-bottle program. Some nights, guests will have the chance to taste powerful, decadent wines that they might not be able afford by the bottle. But just as often, it’s an education, a chance to taste history, and a chance to learn the story of a wine that might hardly exist anymore. Anyone can love a Ridge Monte Bello from a classic vintage, but a glass of that 1982 engenders just as much admiration for Draper, if not more.

No bigger than six

The limit is six liters. That’s the largest bottle that Madrigale feels comfortable pouring by the glass. He has attempted to pour directly from a nine-liter bottle, but “it was a joke. It was like pouring a glass of wine from a fire hose.” Why not use a decanter? “I never do that. That takes away the theater for me. You must pour from the large format to give your guests the buzz.”

The easiest large format to sell, Madrigale has found, is Chateauneuf-du-Pape. “It always moves,” he said. “Next is anything aged fifteen years or older. After that, Barolo. And the hardest wine to sell from large format is Gewurztraminer.”

That doesn’t mean Madrigale won’t try. He’ll pour large formats of Gewurztraminer, Cabernet Franc from Long Island, whites from Alto Adige, Blaufrankisch from Austria. “People are adventurous,” Madrigale said. “They want to taste the world, and they don’t often get the chance to do it.”

The program’s popularity has not convinced Bar Boulud to move the price. All big bottle pours range from $15 to $29. Madrigale said that the program is not a money maker. Sometimes a bottle will turn a small profit, but most break roughly even. That makes the impact of the program more difficult to measure, but consider that our waiter estimated that sixty percent of his guests on a given night will know about the big bottles. Are some showing up primarily because of the big bottles? Undoubtedly.

No rest for the somm

Madrigale said that the program has become a “monkey on my back, because I can never rest from buying large formats. I open one every day.” In the early days, he found a lot of aged Chateauneuf-du-Pape in the marketplace for favorable prices. He recalled an abundance of Pierre Usseglio, Beaucastel, and Vieux Donjon in particular. These days, he hounds the auction circuit while keeping open lines with distributors, well known collectors, and the producers themselves.

Most sommeliers find a different line of work within the wine industry before turning 40. Spending an evening at Bar Boulud is all one needs to understand the reason. Madrigale is almost always there, and when he’s not, he’s working on maintaining one of the hottest wine programs in the country. Eventually, he will step aside, and he will leave a legacy: He has made wine more accessible, by price, by producer, by the stories that reveal what wine is all about. And he has reminded us that we need no special occasion to open a special bottle. The bigger the better.