Backstage at the world’s largest wine competition: two incredible days of judging at the International Wine Challenge in London. Continued from Part 1: Initiation

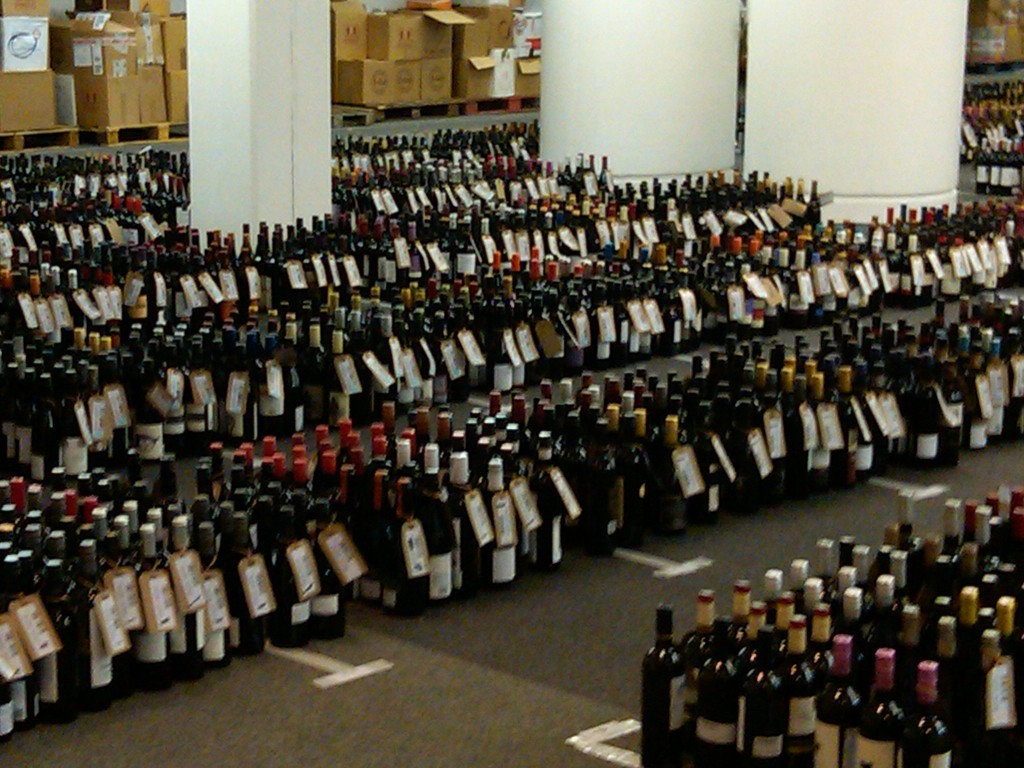

During the judging, no judges are allowed into the vast warehouse space that holds all of the wines. Last April, there were more than 12,000 wines entered into the IWC competition. At four bottles of each, we are talking about 55,000 bottles of wine. Every one had to be photographed, identified with a URN (unique reference number), and labeled with a code number that traced it back to the URN and the company that sent in the wine. Then the bottles were placed in a defined order in the “picking area” till they were selected for judging.

Our judging tables were set in rows in a large, open-ended but very basic exhibition room. It overlooked part of the gigantic lower floor that had been turned into a wine warehouse for the event. All wines are tasted blind at IWC, so runners brought in all the flights of wines in coded wrappers. It seemed to me that most flights consisted of around a dozen wines, though in actuality they were often larger or smaller. If our panel thought a wine was technically flawed we asked for another sample, and the runners were supposed to be able to zoom off to the shelves, find the bottle and return to us in the space of a minute—which did sometimes happen. With each panel assigned over a hundred wines a day to judge, there was no time to waste.

As the day went on, some adjustments were made depending on how fast some tables were working in comparison to the others. The runners that brought our wines were volunteers, people who took a few days off work to learn about wine; they were allowed to taste all the wines left in the bottles after the judges had poured their portions. It helped to befriend our runners, because they would deliver wines very quickly, and forage for more water and crackers when needed. Through the runner, we could also plead for a change in our program, like the times when we were longing for crisp, white wines after half a dozen flights of tannic reds. Sometimes the pleas were answered by the powers-that-be in the back rooms (the chairmen); mostly they were not, and we were kept to our original assigned flights.

We got into a rhythm: pour the wine, check the color, swirl, sniff, sip, and spit. Think and write. The killer: we had to write legibly and without abbreviations in case they decided to use our tasting notes in the interim judging, or to put on the IWC website if the wine was awarded a medal in the final judging.

The first days (when I was there) were basically elimination rounds. We were required to have compelling explanations for why a wine should—or should not—go on to the finals. Each “commended” wine was later re-tasted by the people judging in further rounds. Other wines were also re-tasted by the more senior judges, either to make sure they should be out of competition, or in case of any controversy on the floor.

During our judging, as I said before, all wines were tasted blind, but we were told something about the general category of each wine flight. The first morning, we started with Champagne—probably to get us in a good mood. If so, it worked. The next categories my table evaluated were New Zealand Pinot Noirs, Bordeaux varietals from Mendoza, Hungarian Chardonnays, Sicilian Nero d’Avolas, Italian Syrahs, etc., etc. We never knew what the next flight would bring.

At some point we were given a lunch slot; when it was time, we made our way through a maze of courtyards and stairwells to a restaurant where a set meal had been ordered for us. By then we were all glad to sit down and refuel with a hearty lunch. Having no sense of direction, I had made sure to keep close to someone who had been there before; I heard that a few people got lost on the way. Over the meal, there were also stories of former judges who had disgraced themselves by not spitting enough during the tastings, or who had fallen asleep with their heads on the tables. (I vowed not to become legendary in this way.)

At some point we were given a lunch slot; when it was time, we made our way through a maze of courtyards and stairwells to a restaurant where a set meal had been ordered for us. By then we were all glad to sit down and refuel with a hearty lunch. Having no sense of direction, I had made sure to keep close to someone who had been there before; I heard that a few people got lost on the way. Over the meal, there were also stories of former judges who had disgraced themselves by not spitting enough during the tastings, or who had fallen asleep with their heads on the tables. (I vowed not to become legendary in this way.)

Scarcely an hour after leaving, we were back in panel formation at our judging tables. The panel chairpersons were the keys to the success of each table. They could be men or women, they could range from informal to militarily precise in their leadership style. But they had to keep us moving forward at a good pace, encourage the exchange of ideas without getting chatty, and be the ultimate arbiters when their judges gave wildly divergent opinions. (If they really found we were flagging, they had the power to take us over to the side of the room for a quick tea break—we did get one once, and it was incredibly welcome.)

Logistics, as I mentioned, are a huge part of the competition. After I finished my two days of judging, I was allowed to go around the storerooms with Chris Ashton. He told me that the IWC had started in London 28 years before. It is held here in part because this is a fairly neutral place: very little wine is produced in the UK, so there is no local partisanship when it comes to judging, even if the lion’s share of the judges are from the UK.

As we wandered around the gigantic storehouse with its shelving racks and floors all covered with coded bottles, Ashton also explained IWC’s recycling initiative, of which he is deservedly proud. Unused wine in bottles is sent to a company that produces gourmet sauces and reductions. All the bottles and packing materials are recycled. Even with tens of thousands of wines, he manages to keep the trash load to one dumpster for the whole event.

Though the actual judging may take only two weeks, IWC activity goes on year-round, with announcements of awards, an award dinner, and wine collecting for the next year’s competition. As a wine judge, toward the end of the first day I wondered why on earth anyone would do this to themselves for two whole weeks: stand around a table and put a hundred wines a day into their mouths. After the second day, I was pleased it was over, and pretty proud of myself for having completed my stint.

Becky Sue Epstein is Palate Press’s International Editor. An experienced writer, editor, broadcaster, and consultant in the fields of wine, spirits, food, and travel, her work appears in many national publications including Art & Antiques, Luxury Golf & Travel, Food + Wine, and Wine Spectator. She began her career as a restaurant reviewer for the Los Angeles Times while working in film and television.

Becky Sue Epstein is Palate Press’s International Editor. An experienced writer, editor, broadcaster, and consultant in the fields of wine, spirits, food, and travel, her work appears in many national publications including Art & Antiques, Luxury Golf & Travel, Food + Wine, and Wine Spectator. She began her career as a restaurant reviewer for the Los Angeles Times while working in film and television.