This simple act of respect brings us closer to understanding First Nations and Indigenous citizens

British Columbia, the westernmost province of Canada, is a place of beauty, wilderness, vast lands, mountain ranges, and commerce. Stunning vistas are everywhere, the Pacific part of the landscape and world-class skiing found less than an hour outside the city of Vancouver, known as the Hollywood of the Pacific Northwest for the number of films being produced there annually given the tax credits granted by the Canadian government.

Here in British Columbia and the rest of Canada, meetings, conferences, festivals and sometimes even a simple meal is opened with an acknowledgment of the people who came before, those indigenous tribal bands that called these lands home. Born out of the 2015 recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the acknowledgment of First Nations tribal bands and the indigenous settlers in general, “opens a dialogue and is the first step to respecting the First Nations and their lands,” says Ryan Rogers, head of The Indigenous Tourism Association in Canada. I let him know how moved I was by the acknowledgements and he let me know that even the Canucks hockey team opens with one before each game.

In Vancouver, the indigenous people that are acknowledged are the Mesqueum, Squamish and Toleil-Waututh tribal bands. Rogers, a Musqueum tribal member, says that the real question is “what’s next?” Indigenous tourism has grown significantly over the past few years and notably, boomed during the pandemic. “Visitors seemed to want to connect deeper to the lands to which they traveled,” says Rogers.

He pointed out that it was preferable to have a local tribal representative make the acknowledgment, but, if that protocol is not an option, any meeting leader could undertake the acknowledgment with a little research. Schools like The University of British Columbia or The University of Saskatchewan are great resources for tribal history, Rogers pointed out, and that’s where anyone wanting to incorporate acknowledgement into an opening speech. If not a member of the local indigenous group, the representative can not welcome guests to the territory, they simply acknowledge the history that came before.

An example of an acknowledgement would be something like the following: “I would like to acknowledge the Bedegal people that are the Traditional Custodians of this land. I would also like to pay my respects to the Elders both past and present and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are present here today.”

British Columbia is also home to the Okanagan Valley, the western wine country of Canada and an area producing fantastic Pinot Noirs and other varieties from dozens of estates complete with resort-style lodging and upscale fine dining. Noticeably different from Napa in the fact that, not only can you have lunch, taste wine, and stay at the same stunning winery, but prices are markedly lower and, yes, Canadians can be much easier to deal with than jaded wine snobs one may encounter elsewhere.

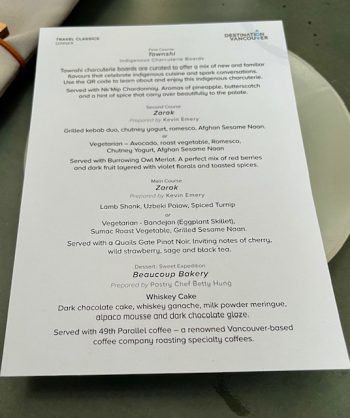

It was in the Okanagan (I love this rhythmic indigenous word) that I first became aware of the attention given to what were then called First Nations people; now expanded to include the Indigenous population as a whole. It was at a winery called Nk’Mip Cellars, owned by the Osoyoos Indian Band, that not only had an indigenous winemaker but, after tasting, sent us to a restaurant nearby serving a traditional indigenous menu, including fry breads, wild berries, game meat like elk and bison, as well as fish and bivalves sourced locally. It was eye-opening; not just a nod to the first settlers, but an embrace of the culture, agriculture, and foods of those that first made this land their home.

British Columbia and the rest of Canada have not always been respectful of their indigenous roots. Flipping through TV channels recently, I stumbled on a film that recounted the early days of its heroine, living on a reservation in Canada, when she and her siblings were taken from their family under the guise of protecting the children from an unfit mother. They were then adopted out through a system that dispersed native children throughout the country so that they could be adopted and raised by white, wealthier families. In the film, the lead female was taken from her family at around five years old and raised in a strict Jewish family, embracing all of their traditions and beliefs. She is about to be married and decides she wants to discover her true roots, which are quite different from the way she was raised in urban Toronto.

Of course, these acknowledgment tributes do not make up for the abhorrent treatment of indigenous people and the manipulation of their children through adoption or the forced commitment of children to residential schools that would educate them in what were considered civilized ways of living. Ripped from their families in the name of Christianity to attend religious schools funded by the Canadian government that numbered up to 80 between 1867 and 1939, almost 4100 native children were lost, died, or unaccounted for in the history of the residential schools; a blight on the history of Canadian indigenous relations.

The Indian bands and land names that were mentioned each time an acknowledgement is made before a meeting can be complicated, hard to pronounce and take a bit of research. While not every member of the congregation will remember the tribal names, they will remember the feeling of undeniable respect for the people that walked and worked the lands many years ago. Sometimes the acknowledgement is part of a prayer, sometimes part of a greeting or opening of an event, but it always makes everyone in the room learn a little bit more about the indigenous past.

The Flying U Ranch, the oldest guest ranch in North America, was first a trading post in 1849, and has welcomed guests to ride, hike, and be a cowboy for the last 100 years. It is designed as a frontier town with small cabins and communal bathhouses, a central dining hall, and a saloon, and has 110 horses and 60,000 acres of open space in the Cariboo region of British Columbia. It is a remote, charming ranch where horses, dogs, and people roam free.

Dining here is elevated for a guest ranch and before each delicious meal, Cowboy Steve or another staff member gracefully acknowledged the indigenous people and the land that had been theirs. Everywhere we went, acknowledgment was part of the program and the solemnity of thinking of the original people of these lands roaming, hunting, gathering, farming, riding horses, and raising families, made every meal or occasion a reason for respect and remembrance.

Much is needed to be done to repair the damage and hurt done through governmental programs but current day Canadians have embraced the reparations necessary to start the healing, beginning with acknowledgments.