Trying to navigate Piedmont by using GPS is like asking your high school Spanish teacher to translate street talk in the heart of San Juan. You’ll get some things right, some wrong, and you’re likely to eventually make an embarrassing mistake.

And so we were about 40 minutes late in our visit at Giuseppe Cortese, a small producer of Barbaresco, touted as traditional and terroir-driven. We had relied on new technology in a region doggedly holding to traditional techniques. The joke was on us, right?

It turns out that the analogy doesn’t fit quite as snugly as I first suspected. Even Piedmont is going modern; that’s not surprising for those who drink the score-buster wines that come carefully polished with all the accouterments provided by a cellar full of new wood. But even the chest-thumping traditionalists are feeling the pull to “modernize”, whatever that means.

It turns out that the analogy doesn’t fit quite as snugly as I first suspected. Even Piedmont is going modern; that’s not surprising for those who drink the score-buster wines that come carefully polished with all the accouterments provided by a cellar full of new wood. But even the chest-thumping traditionalists are feeling the pull to “modernize”, whatever that means.

Cortese is a perfect example. We met Giuseppe as he worked the winery, then tasted his portfolio with his lovely daughter Tiziana. She was generous enough to pull a range of older vintages alongside the new releases. She proudly explained that while some of the Barbera might see barrique, the Barbaresco sleeps in large casks. The Barbarescos were beautiful, structured, wonderfully classic Nebbiolo, without so much as a whisper of oak. They bore moderate alcohol levels and were not to dense and concentrated as to lose their sense of place. “Tradition comes first,” Tiziana explained.

I was surprised, then, to later visit the Cortese website and see a different kind of explanation of winemaking practice. “Cortese company production is characterized by the mix of traditional methods and the implementation of modern wine processing technics (sic).” Why, I wondered, would they tout modernization when the family speaks so fondly of tradition?

One of the finest wine bloggers currently writing, Alfonso Cevola, offers his take on what he dubs the “tweens.” Cevola is focusing on Montalcino and Brunello, but the parameters he lays out can be assigned to winemaking around the world. Cevola writes of the traditionalists, who almost obsessively seek to uphold historical practices and sense of place. He writes of the modernists; you can guess what that means. And he writes of the “tweens,” those producers who fall somewhere in the middle. Cevola accurately notes that the tweens represent the largest category by far, with some tweeners offering a mostly modern style, while others are largely traditional.

Cevola’s provocative piece called to mind my visit with the Corteses. How could they be tweens? More importantly, is there a problem with being a tween? Cevola described it as being in a kind of wine purgatory.

My answer will surprise some friends who love natural wines. Here it is: If you want wine with a sense of place, you’re better off in the tweens. Ultra-modernists will obscure a wine’s sense of place, but sometimes, so will the ultra-traditionalists.

Now, I should clarify that nothing is as important to me in wine than a sense of place. I’d rather drink a wine that is intellectually stimulating than one that is simply delicious. I tend to favor so-called natural wines over the glossiest of the modern offerings.

But if we’re going to allow the Alice Feirings of the world set the terms of the category of what “natural wine” is, then we should recognize that many “traditionalists” in Cevola’s framework are actually tweens. Cortese’s Barbaresco is non-filtered, spontaneously fermented, aged in botti. It is picked before the grapes become raisins. It evokes Rabaja with admirable clarity. But the Cortese family openly declares their own practices as a mix between traditional and modern. I wonder if there is a bit of a backlash to the most ardent naturalists.

But if we’re going to allow the Alice Feirings of the world set the terms of the category of what “natural wine” is, then we should recognize that many “traditionalists” in Cevola’s framework are actually tweens. Cortese’s Barbaresco is non-filtered, spontaneously fermented, aged in botti. It is picked before the grapes become raisins. It evokes Rabaja with admirable clarity. But the Cortese family openly declares their own practices as a mix between traditional and modern. I wonder if there is a bit of a backlash to the most ardent naturalists.

Cortese wants customers to know that the wines are representative of place, but I suspect that pushing the natural label could invoke the wines of, say, Frank Cornelissen. The ultra-naturalists have gained a cult following that approaches something like a religious congregation. Unfortunately, the four occasions I’ve had to taste Cornelissen’s wines have all seen them utterly shot and undrinkable. I recognize that on occasion, those wines can sing. It is too bad that the occasions are as fleeting as they are.

This is not to pick on one producer or draw a line in the sand. Every time I encounter a bottle of Cornelissen’s wine, I am eager to taste it. Wine, however, requires at least minimal intervention to become a drinkable product. The most dogmatic adherents to the natural movement use Cornelissen as the standard. So while the wines of Giuseppe Cortese are by many standards traditional, they are nowhere near as untouched by man as the truly natural wines of Frank Cornelissen and his ilk.

So if we accept that the tween category is larger than even Cevola might describe, the challenge becomes in seeking out wines of place. Some tweens seem to pour the land straight from the bottle. Others taste like creme brulee. Buyer beware.

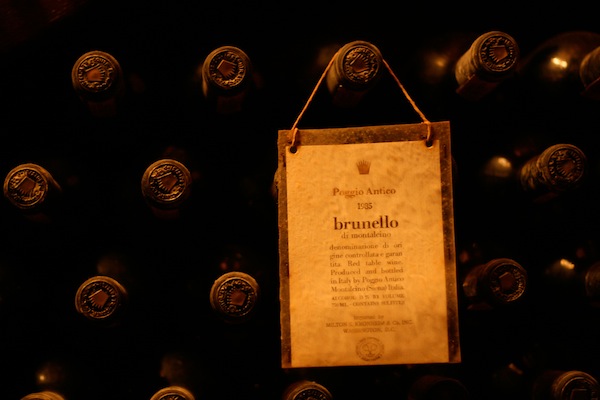

During a visit to Tuscany five years ago, I was surprised that most Brunello producers we visited proudly declared that they used a mix of traditional and modern techniques. But unlike the excellent wines at Cortese, the wines we encountered tended to be modernist in approach, with the ostensible traditionalism nothing more than marketing filler. Poggio Antico, for example, showed off a cellar of Brunelli going back decades. With a shiny new cellar and barrique from floor to ceiling, the traditionalism seemed confined to those dusty bottles—not the new ones rolling off the line. The wines were very solidly made, but not inspiring, not special.

During a visit to Tuscany five years ago, I was surprised that most Brunello producers we visited proudly declared that they used a mix of traditional and modern techniques. But unlike the excellent wines at Cortese, the wines we encountered tended to be modernist in approach, with the ostensible traditionalism nothing more than marketing filler. Poggio Antico, for example, showed off a cellar of Brunelli going back decades. With a shiny new cellar and barrique from floor to ceiling, the traditionalism seemed confined to those dusty bottles—not the new ones rolling off the line. The wines were very solidly made, but not inspiring, not special.

The default answer in the cellars of Montalcino is something along the lines of, “We bring the best of history with the advancements of modern technology.” Sadly, most of the time it’s a cynical ploy to convince consumers the wines are more traditional — more evocative of place — than they are. Cevola knows all too well that many Brunelli these days could hardly get picked out of a lineup.

“Take a good look, ma’am, at these five reds. Is the one you ordered last night standing in front of you now?”

“I’m sorry, they all seem the same.”

In the Finger Lakes, where I live and write, most producers are decidedly modern in approach. Recently, winemaker Johannes Reinhardt of the Anthony Road Wine Company decided to employ spontaneous fermentation for his Rieslings. It’s not that Johannes thought commercial yeast were taking a wine’s sense of place away; rather, he felt that commercial yeast was perhaps creating a “uniform” that limited the range of expressiveness. Plenty of German winemakers use commercial yeast; you’d hardly claim that every one of those wines is disqualified from sharing a sense of place. In Burgundy, adding sugar (chaptalization) is hardly a stride in the natural direction, but do you find Burgundy lacking in terroir? These are tweens that we’re talking about, but they are perfectly capable of delivering something unique.

Reinhardt finds that spontaneous fermentation allows his Rieslings to be even more expressive of their home. He’s excited about the results. Many of his techniques in the cellar would still be described as modern; he’s a tween, creating Riesling with a glorious sense of place.

With the debate in recent years about natural wines, the tween category is prone to broad-brushing. I have learned that it’s a mistake to discount some tween wines simply because they employ a technique that the winemaker’s predecessors did not.

And the Piedmontese still laugh at those of us who rely on GPS. They rely on getting to know the land and occasionally asking a neighbor for directions. Of course, they’re driving modern vehicles to get around. The world is filled with tweens, indeed.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/evan.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Evan Dawson is a news anchor / reporter at the ABC News affiliate in Rochester, NY. He has reported on public policy and politics for more than 10 years. He is the Managing Editor of the New York Cork Report, as well as the author of the critically acclaimed Summer in a Glass: The Coming of Age of Winemaking in the Finger Lakes.[/author_info] [/author]