A wave of headlines over the past several weeks has undoubtedly caused concern in many pregnant women.

Those headlines are based on a new study by a team led by Dr. Haruna Feldman at the University of California, San Diego concerning the effects of alcohol on a developing fetus. “Study: No Amount of Alcohol During Pregnancy Safe,” one headline reads. “One Drink is Too Many,” another declares. Those headlines are based on the Feldman team’s conclusion, which says, “Women should continue to be advised to abstain from alcohol consumption from conception throughout pregnancy.”

This is the third scientific study in the past two years that has generated headlines related to the effects of light drinking during pregnancy. Prior to these studies, very little research focused on such effects.

But the news media has not provided helpful analysis. A reporter for Medical News Today online wrote a story in October 2010 with the headline, “No Evidence that Light Drinking In Pregnancy Harms Children’s Development.” Fifteen months later, that same reporter wrote a story titled, “No Safe Level of Alcohol During Pregnancy.” Apparently it never occurred to this reporter that readers might appreciate a comparison of these two studies.

It’s an important comparison to make; multiple doctors have told me that women regularly ask if they should have an abortion because they had a drink or two before they knew they were pregnant. The reporting of these studies could similarly factor in pregnant women’s decision-making.

A review of current research from a team at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto sums it up best:

Exposing one’s own child, albeit unintentionally, to a teratogenic substance [one that can potentially cause birth abnormalities] can cause severe guilt and anxiety in the mother. Evidence- based information regarding the actual magnitude of the risk of low level alcohol exposure during gestation is necessary in order that women can be counseled accurately and sensitively, and to avoid potentially harmful feelings of guilt and stress in the mother, which in some instances may lead to the unwarranted termination of pregnancies. On the other hand, misinformation derived from inadequately designed studies that minimizes the risk of low level exposure can also be extremely counterproductive because mothers may be encouraged to continue drinking throughout their pregnancy, potentially causing harm to the fetus.

Another way to say this is that it’s dangerous to tell women it’s safe to drink alcohol during pregnancy, but it’s also dangerous to fear-monger, which could scare women into having abortions.

In reviewing the three recent studies, we find that the Feldman study is hampered by numerous limitations. In fact, the Feldman study was not designed to study the effects of light drinking during pregnancy at all. But it is already gaining momentum with those who cite it as research that demonstrates the dangers of even the lightest drinking during pregnancy. The previous two studies did, in fact, focus on the effects of light drinking during pregnancy, with much different findings.

None of the studies establishes a safe level of drinking for pregnant women. However, these studies add some important detail to what we know about the effects of light drinking.

Let’s start by examining what the three studies were all about, and whether there are issues with each study’s credibility.

Robinson study, Australia, 2010

Study name: Low-moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and risk to child behavioural development: a prospective cohort study

Study name: Low-moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and risk to child behavioural development: a prospective cohort study

Published in: BJOG, International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Focus: Effects of alcohol during pregnancy on children’s behavior

Sample size: 2,370 children

Evaluation period: Children age 2 through 14, evaluated every two or three years

Definition of “light drinking”: 2 to 6 drinks per week

Dr. Monique Robinson’s team in Australia studied the behavior of children over the first 14 years of the children’s lives, looking for effects from their mothers’ consumption habits during pregnancy. They used highly regarded models for assessing behavior, and they had a statistically significant control group of non-drinking mothers. In fact, the Robinson team examined kids born to non-drinkers, light drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers.

The Robinson team found that the children born to light drinkers early in pregnancy tended to behave better, or “more positively”, than the children of mothers who did not drink at all early in pregnancy. Children born to heavy drinkers had all kinds of problems. The kids of light drinkers showed fewer emotional and behavioral problems through childhood and adolescence than the kids of non-drinkers. The kids of light drinkers were less aggressive and less likely to suffer from depression.

This was a large sample size, and it tracked children for a long time relative to other studies in the field. Dr. Robinson concluded, “We need to be cautious about generalizing the effects of a heavy alcohol intake to a light consumption of alcohol — they are not equal.” She warned of the dangers of heavier drinking during pregnancy, and said that more study was warranted.

Critics point out that the children born to light drinkers in the Robinson study tended to come from families on the higher end of the socioeconomic scale. That means their mothers were more likely to be in good general health and less likely to be doing drugs or consuming other teratogens. So perhaps the women in the Robinson study were better equipped to handle a drink on occasion during pregnancy.

Kelly study, England, 2011

Study name: Light drinking during pregnancy: still no increased risk for socioemotional difficulties or cognitive deficits at 5 years of age?

Study name: Light drinking during pregnancy: still no increased risk for socioemotional difficulties or cognitive deficits at 5 years of age?

Published in: Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health

Focus: Effects of alcohol during pregnancy on children’s behavioral, emotional, and intellectual development

Sample size: 11,513 children

Evaluation period: Children from birth to age 5, evaluated at regular intervals

Definition of “light drinking”: No more than two drinks per week

Dr. Kelly tells me that this study is ongoing with these children, offering a continuing look at the effects of alcohol during pregnancy. The large sample size allowed the Kelly team to study the effects of all levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. They worked with a statistically significant control group of non-drinking mothers.

No surprise, the Kelly team found that children born to heavy drinkers have a higher likelihood of suffering in various forms of development. But Kelly’s team made a similar finding to the Robinson team in comparing the thousands of other children in the study: turns out that over the first five years of their lives, children born to light drinkers tended to perform better on a range of tests than children born to non-drinkers. Children of light drinkers had slightly better vocabularies, could reconstruct patterns and colors more effectively, and could recognize picture similarities more easily. And those children were 30% less likely to have diagnosed behavioral problems.

Critics of the Kelly study generally voiced the same concerns as those who criticized the Robinson study: too many children born to light-drinking mothers, they argued, were born into the higher end of the socioeconomic scale. It was perhaps not a representative sample of the population, because the kids were more advantaged.

But when I contacted Dr. Kelly to ask about this issue, she indicated that the criticism is misplaced. That’s because her team was aware of this issue, and attempted to account for socioeconomic factors before drawing conclusions.

“Light drinking (during pregnancy) was not associated with consequential developmental difficulties, regardless of social position,” she explained. “We did not find different effects of alcohol according to whether light-drinking mothers had a university versus high school education.”

She added, “Our work uses data from a large representative population-based sample of families. However, alcohol consumption is socially patterned, with light-drinking mothers more likely to be socially advantaged compared with non-drinkers and heavy drinkers.”

Dr. Fred Bookstein, a Professor of Statistics at the University of Washington, offered high praise for the Kelly team’s work. Dr. Bookstein’s work dates back many years, and he has focused his work on the issue of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS).

Dr. Fred Bookstein, a Professor of Statistics at the University of Washington, offered high praise for the Kelly team’s work. Dr. Bookstein’s work dates back many years, and he has focused his work on the issue of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS).

“This is such a good study that it should shut down this line of research,” Dr. Bookstein said, adding, “It is no longer valid to argue that we don’t know enough about low-dose drinking during pregnancy or that the known effects of binge drinking may penetrate to low-dose drinkers somehow.”

Dr. Kelly wants more time to evaluate the children, and is not taking an advocacy position based on her research.

Feldman study, California, 2012

Study name: Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Patterns and Alcohol-Related Birth Defects and Growth Deficiencies: A Prospective Study

Study name: Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Patterns and Alcohol-Related Birth Defects and Growth Deficiencies: A Prospective Study

Published in: Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research

Focus: Physical abnormalities in infants related to alcohol consumption during pregnancy

Sample size: 992 children

Evaluation period: Children evaluated shortly after birth

Definition of “light drinking”: Less than one drink per day

Dr. Haruna Sawada Feldman’s team in California studied the results of 992 children born between 1978 and 2005. They worked with women who were drinking lightly, moderately, and heavily at some point during pregnancy. They did not follow the children for multiple years to check on development.

This study was all about evaluating how alcohol might affect the fetus at different points during pregnancy. And what the Feldman team discovered was that the second half of the first trimester appears to be the most sensitive. That’s the kind of big-deal finding that is potentially groundbreaking. They divided the subgroups to examine alcohol intake at various levels, and Dr. Feldman told me that she finds this aspect to be the most noteworthy.

“The most significant finding from this study was that we were able to quantify specific risks for alcohol-related minor malformations and growth deficiencies based on specific patterns and timing of exposure during pregnancy,” Dr. Feldman explained.

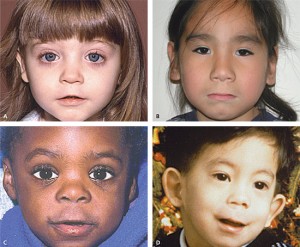

It’s important to understand exactly what the Feldman team was looking for. In order to make a diagnosis of FAS at birth, an expert known as a dysmorphologist must study the physical traits of the child that can be affected by alcohol. These traits can be physical markers that portend long-term mental and emotional disabilities. Along with birth length and weight (which tend to be lower when alcohol impacts a developing fetus), the examiner is looking for three tell-tale physical traits:

- A smooth or shallow dimple below the nose, which is known as smooth philtrum

- A markedly thinner upper lip, known as thin vermillion border

- Small or narrow eyes, known as short palpebral fissures

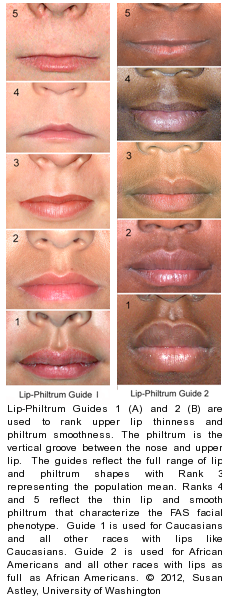

It’s not enough to determine that alcohol caused these features if a child is born with only one of them, because some children will naturally be born with them. Older standards require at least two of the three features for a FAS diagnosis. The most rigorous standard was developed by Dr. Susan Astley at the University of Washington, one of the pioneering researchers in this field. Dr. Astley’s definition requires all three features for a diagnosis of FAS; she’s found that fewer than half the children born with two out of three will have FAS. However, when a child has all three, there is a 95% probability that the child will have FAS.

Strangely, the Feldman team only reported the incidence of these features individually. Given the team’s conclusions, and given the news headlines touting this study, one might assume that many of the 992 kids were born with all three facial features related to FAS, and many more were born with two out of three.

So I contacted Dr. Feldman to find out how many kids of the 992 were found to have all three. The answer: 4 children. That’s less than one half of one percent. Another 10 were born with two out of three features. In an email, Dr. Feldman explained, “I did not look at the fetal alcohol syndrome diagnosis because the paper focused on each outcome individually, so out of the entire sample, I do not know how many had a FAS diagnosis.”

When I shared this with Dr. Astley, she said it was surprising. “I respect my colleagues and I think this is an interesting study,” Dr. Astley said, “but it is only the cluster of all three features together that can be causally linked to prenatal alcohol exposure.”

Another question naturally emerged. Remember, the headlines warned that this study found “one drink is too many” for women who are expecting. So I wondered, how many of the four infants born with almost-certain FAS, and how many of the 10 kids born with possible FAS, were born to mothers who only drank lightly during pregnancy?

Dr. Feldman declined to answer that question, indicating that it might be addressed in a future paper. FAS is not always a simple yes-or-no diagnosis; experts say there is a spectrum known as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders that can reveal severe to mild effects of drinking during pregnancy. Some children might be affected both physically and mentally; others might show only physical or only cognitive defects. Is it possible that the Feldman team will dispute the notion that physical features must be seen in clusters to determine alcohol as the cause? They don’t say so in this paper, and so we’ll have to see what Dr. Feldman publishes going forward.

Drilling into the details, we find other limitations with the Feldman study. For example, in many cases, the experts who studied the babies’ faces used methods that are now considered outdated. The old way of doing things — asking an examiner to look at a child’s face and make an assessment without any kind of scale to base it off of — was not very reliable. That’s why Dr. Astley developed a five-step scale to help dysmorphologists. Keep in mind, some kids will be born with these abnormal features even if their moms didn’t drink at all. For example, less than one percent of the general population will naturally be born with the smoothest philtrum (dimple under the nose), but Dr. Astley also estimates that 5-10% of the population will naturally be born with the second rank of smooth philtrum, which qualifies as a marker of FAS. In the Feldman study, 1.9% of kids born to light-drinking moms had smooth philtrum, and 7.8% of kids born to heavier-drinking moms had smooth philtrum. It shows a correlation; as alcohol intake increases markedly, more kids are born with smooth philtrum. But both numbers fall within the range of what might occur naturally, and certainly the light-drinking moms didn’t produce an eye-catching number of kids with this feature.

“We have to be extremely careful not to over-interpret studies like this one,” Dr. Astley said, indicating that the Feldman study does not have the ability to prove that alcohol caused the facial malformations. “This study is a nice addition to the FASD literature, but we have to be careful not to interpret the associations reported in this study as ‘causal’.”

Even more concerning, there was no control group of non-drinking mothers. Whereas the Robinson and Kelly studies benefit from a statistically significant group of moms who abstained, the Feldman study does not. Without a control group of non-drinking moms, there is no helpful comparison with the children born to light-drinking moms. For example, a control group of light-drinking moms would have helped indicate whether the 1.9% of children were born with a natural smooth philtrum, or one caused by alcohol.

Even more concerning, there was no control group of non-drinking mothers. Whereas the Robinson and Kelly studies benefit from a statistically significant group of moms who abstained, the Feldman study does not. Without a control group of non-drinking moms, there is no helpful comparison with the children born to light-drinking moms. For example, a control group of light-drinking moms would have helped indicate whether the 1.9% of children were born with a natural smooth philtrum, or one caused by alcohol.

“We are also looking into non-drinking women as well, but that’s for a different study,” Dr. Feldman told me.

The Feldman study is also limited by the very same thing that critics pointed out regarding the Robinson and Kelly studies: It was not a representative population sample. The 992 mothers from the Feldman study contacted a telephone help line because they were concerned about what they had put into their bodies. More than 23% were doing drugs – cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, or marijuana. Another 4% had ingested other potentially harmful substances. The Feldman team considered those things, and didn’t find them to strongly impact the infants’ development of physical features related to FAS. But you could certainly never say this was a representative population sample, from which it’s appropriate to offer wide-ranging conclusions.

The Feldman study is also limited by the very same thing that critics pointed out regarding the Robinson and Kelly studies: It was not a representative population sample. The 992 mothers from the Feldman study contacted a telephone help line because they were concerned about what they had put into their bodies. More than 23% were doing drugs – cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, or marijuana. Another 4% had ingested other potentially harmful substances. The Feldman team considered those things, and didn’t find them to strongly impact the infants’ development of physical features related to FAS. But you could certainly never say this was a representative population sample, from which it’s appropriate to offer wide-ranging conclusions.

And the critics who complained that the Robinson and Kelly mothers were too upper-crust have gone silent regarding the Feldman mothers, who came from the low end of that scale.

Dr. Astley points out that some of the Feldman study’s limitations are not the fault of the researchers. For starters, a lot has changed since 1978. As mentioned, the methods that experts use to evaluate a child have become much more precise. Also, the team is missing data regarding eye size for 212 of the children because those children were crying or uncooperative to the point that the dysmorphologist couldn’t take a useful measure.

One might begin to wonder how a study of this nature could ever lead to the conclusions and headlines that we’ve seen. Dr. Bookstein examined the study and found it was simply never constructed to make a comment about light drinking during pregnancy.

“It appears to have been a competently run study,” Dr. Bookstein told me, “but in its actual findings there is nothing particularly surprising, no real news. Yes, really high alcohol exposure risks substantial physical effects on the fetus. On the other hand, to conclude that women should abstain from alcohol throughout pregnancy appears unjustified.”

I asked Dr. Bookstein to further explain why the conclusion made by the authors of this study “appears unjustified.”

“The way you decide if there is an effect at the lowest dose is to analyze your study in the manner that the Kelly study did,” Dr. Bookstein explained. “You have to compare outcomes between two actual subgroups: the group having zero dose (of alcohol) and the group combining the lowest nonzero doses that your data sheets permitted.”

He added, “If you are going to advise women to abstain, you need explicit evidence that even the lowest nonzero dose has consequences, and the only way to get this evidence is to check explicitly. The research described here should not and does not persuade the competent reader that there is explicit evidence of damage at low doses.”

If anything merited a headline from this study, surely it was the fact that the Feldman team saw a more sensitive effect of alcohol during the second half of the first trimester. But the media’s focus shifted when the Feldman team concluded that their study showed “no safe threshold” for alcohol consumption during pregnancy. They weren’t looking for one, and based on the myriad variables in the way our bodies work and our lives unfold, they would never find one anyway. That added line clouded the entire purpose of the study, and as a consequence, the news media missed or misinterpreted the point.

The news media’s responsibility

It’s a lot to digest, and it’s instructive to examine how news reporters disseminate this information to the public. Reporters covering the Kelly study occasionally drew their own conclusions. One headline declared that “Light Drinking During Pregnancy May Be Beneficial for Children.” The reporter might have interpreted the study to mean that the kids performed better on tests because of their mother’s light drinking, but Dr. Kelly never said that. In fact, Dr. Kelly was simply making the point that light drinking during pregnancy did not appear to cause any problems; she was not advocating for pregnant women to pour a drink or two a week.

The headlines regarding the Feldman study have been ominous. The reporting has focused on the Feldman study’s citation of statistical risks as alcohol intake increases. Here’s how the Wall Street Journal reported the findings – see if you can figure out what this means:

For each drink consumed each day over the daily average in the second half of the first trimester, the women’s babies were 12% more likely to have a small head circumference, 16% more likely to have low birth weight and over 20% more likely to have a very thin upper lip or lack of a vertical indentation between their noses and lips. While seemingly minor, those characteristics are typical of fetal alcohol syndrome, or FAS.

What, exactly, is the “daily average” referenced in the article? The reporter doesn’t say. I shared this with three different women in my office, all of them mothers. I asked them to interpret what those percentages mean. All three agreed on what it seemed the article was saying: that 20% of babies will be born with facial features indicative of FAS if their mothers have one drink daily, and 40% would be born with those facial features if their mothers had two drinks daily, etc. Same for birth weight: They thought the article was saying that 16% of babies will be born with low birth weight if their mothers had one drink daily, and that number would increase to 32% with two drinks, 48% with three drinks, etc. Clearly, they thought, the article is saying that large percentages of babies would be born with physical defects based on even a light or moderate level of drinking.

This is a very good example of how poorly the news media handles statistics and research. Context is everything, and in the reporting of this study, context is absent. I picked on the Wall Street Journal in this instance, but you’ll find that nearly every news report on the Feldman study used those numbers without context.

Here’s what the article would have said if the reporter put the numbers from the Feldman study into proper context:

98.4% of mothers who drank light amounts of alcohol daily during the first trimester produced children with no evidence of FAS. Of the 1.6% of children born with such features known as smooth philtrum (the lack of a dimple below the nose) and/or thin vermillion border (very thin upper lip), it is not known how many of those children would have been born with those features regardless of alcohol consumption. It is possible that some or all of the 1.6% features are naturally occurring. The researchers did not explain why they chose not to compare light drinking mothers to non-drinking mothers.

See, not as juicy, is it? But it’s a much clearer picture of what was found. Regarding the increases in chances of a physical abnormality associated with FAS, a properly contextualized article would have said something like this:

Mothers who admitted consuming more than one drink per day during the first trimester (and this group includes binge drinkers) saw the chances of physical abnormalities in their babies rise. For example, in that group including binge drinking moms, 4.7% of infants were born with a thin upper lip, up from 1.3% born to mothers who drank lightly. The study did not follow the intellectual, emotional, or behavioral development of the children born with those abnormalities, nor did it report the number of children found with multiple features related to FAS.

And so on. Does it appear that there is a correlation between heavy drinking and physical abnormalities related to FAS? The Feldman study shows that, once again, the answer is yes. But it seems that news reporters have simply accepted the other conclusions of the research team without drilling into the data.

My colleague Adam Chodak points out that most news reporters are not trained to sift through the dense publications of medical research. To that end, reporters have to rely on researchers to offer cogent, clear conclusions. He’s right. But that does not absolve reporters from asking basic questions and adding context to numbers that might be confusing for most readers.

Conclusions

The Feldman study is already being touted as a breakthrough regarding light drinking during pregnancy. The website for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Experts includes the following line:

Research has demonstrated that FASD can occur in women who drink only a few times or drink small amounts on a regular basis during pregnancy.

When I asked for the research that supports this statement, Program Director Dr. Natalie Brown sent me the Feldman study, “hot off the press,” as she said. She told me it was right on point, but certainly we know that the Feldman study does not demonstrate that FASD can occur if women drink only a few times during pregnancy. If there is other research that does demonstrates this, Dr. Brown did not provide it to me.

We should be careful not to take too much from the Robinson and Kelly studies, as well. Dr. Kelly stressed to me that more research, and more studies, are necessary. Dr. Feldman, who has been accessible and helpful, tells me that her team is already engaged in more study. That’s heartening. Dr. Astley continues to do pioneering work in the field. Dr. Kelly’s team has an enormous sample size from which to draw ongoing observations.

No matter what the future research reveals, it’s almost impossible to envision a scenario when the prevailing medical advice changes. After all, alcohol is a teratogen. In larger doses, we know that alcohol can cause birth defects. Every person’s body is different; every woman processes alcohol differently; no two people consume exactly the same food while drinking; etc. We will never be able to determine a “safe” threshold for drinking during pregnancy. And consider the at-risk women who populated the Feldman study; no doctor would want to counsel those women that “a drink on occasion” is probably fine. Some people can not stop at one drink. Doctors are justified by science in counseling women to avoid alcohol while pregnant.

No matter what the future research reveals, it’s almost impossible to envision a scenario when the prevailing medical advice changes. After all, alcohol is a teratogen. In larger doses, we know that alcohol can cause birth defects. Every person’s body is different; every woman processes alcohol differently; no two people consume exactly the same food while drinking; etc. We will never be able to determine a “safe” threshold for drinking during pregnancy. And consider the at-risk women who populated the Feldman study; no doctor would want to counsel those women that “a drink on occasion” is probably fine. Some people can not stop at one drink. Doctors are justified by science in counseling women to avoid alcohol while pregnant.

But neither should we ignore the research that supports Dr. Robinson’s very important point: Light drinking during pregnancy is not at all the same as heavy drinking during pregnancy. Dr. Abe Lichtmacher, the Chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Rochester General Health Systems, says he hears from women “almost every single day” who have recently discovered that they’re pregnant. “They’ll tell me they had a glass of wine at dinner last night and found out they were pregnant this morning, and they want to know what they should do about it. I always advise them not to panic. You can stop drinking and start focusing on how to have the healthiest pregnancy possible.”

With more responsible reporting from the news media, and further study from the scientific community, women can receive the kind of information that will help them make the best decisions for themselves and their babies.

Evan Dawson is a news anchor / reporter at the ABC News affiliate in Rochester, NY. He has reported on public policy and politics for more than 10 years. He is the Managing Editor of the New York Cork Report, as well as the author of the critically acclaimed Summer in a Glass: The Coming of Age of Winemaking in the Finger Lakes.

Evan Dawson is a news anchor / reporter at the ABC News affiliate in Rochester, NY. He has reported on public policy and politics for more than 10 years. He is the Managing Editor of the New York Cork Report, as well as the author of the critically acclaimed Summer in a Glass: The Coming of Age of Winemaking in the Finger Lakes.