Sour beers, with their bright acidity and vinous, funky qualities, start to bridge the gap between beer and wine. It took a trip to the Great American Beer Festival and several brewery visits (just to be sure…) for me to get a grasp on the movement that presents beer, tarted up a bit.

How to make sour beer

With a few exceptions, the start of a sour beer proceeds like that of a normal beer, with primary (alcoholic) fermentation done with the brewery’s Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain of choice. Pale, red, and even dark beers can be used as a base.

After primary fermentation, the beer is transferred for secondary fermentation (acidification), often in oak barrels. Wild yeasts and bacteria living in the barrels or added by brewers can eat more complex sugars than yeast (remember, the starting product in beer is malted grain, loaded with complex carbohydrates from starch breakdown). Over a period of months or even years, souring microorganisms feast on what’s left over after primary fermentation, converting leftover sugar chains to create refreshing tartness (and a little bit of funk) in the resulting brew.

Sour batch kids

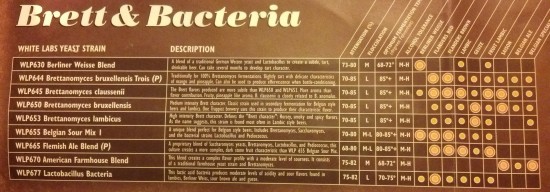

The stars of the show are “wild” yeast and bacteria, so called to differentiate them from brewer’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Brettanomyces, that resilient and funky wild yeast; lactic acid bacteria of the genera Lactobacillus and Pediococcus;and acetic acid bacteria of the genus Acetobacter can all contribute to acidification during fermentation. Studies of organisms that contribute to spontaneous fermentations (such as in the case of lambics) have found hundreds of different species of microorganisms, including Kloeckera, Klebisella, Gluconobacter, E. coli, and more. Just as brewers often culture “house” strains of Saccharomyces, house strains of Brett, Lacto, and, in rare cases, Pedio, are usually used to inoculate beers. In some cases, they have a “house mix” of sour organisms, propagated through barrel after barrel like a sourdough starter.

| Organism | Primary contribution | Secondary contribution |

| Brettanomyces | Funk (barnyard, sweaty) | Acetic acid, ethyl acetate |

| Lactobacillus | Lactic acid | Diacetyl (buttery) |

| Pediococcus | Lactic acid | Diacetyl (buttery) |

| Acetobacter | Acetic acid | Ethyl acetate (nail polish) |

Each organism involved in fermentation brings its own characteristics to the table. Nowadays, brewers can choose fermentation organisms based on their metabolic profiles. For example, while Brettanomyces can ferment sugars into ethanol and acetic acid, it is generally used for its aroma characteristics, producing phenolic products like 4-ethylguaiacol (smoky, clove) and 4-ethylphenol (medicinal, band-aid) and cheesy, sweaty products like butyric acid and isovaleric acid esters.

Exposure to oxygen can make some organisms, especially Acetobacter, produce acetic acid. This compound not only adds tartness, but is also volatile, adding a vinegary tang to the aroma. Moreover, acetic acid can react with ethanol to form ethyl acetate, which smells like nail polish. When found in wine, these two aromas comprise the fault known as volatile acidity.

Wine lovers may recoil (or not) at the presence of Brettanomyces. It’s generally not welcome in wine and as wine ages in the bottle, Brett can create aroma compounds that can be described anywhere from “sweaty saddle” to “barnyard” (the polite descriptor). And while Brett is mostly a no-no in New World wine, infection with Pedio and Lacto can lead to such interesting (if commercially rare) wine faults as ropiness (Pedio), and mousiness (Lacto).

While wine uses lactic acid bacteria (LAB) like Oenococcus oeni to reduce acidity (by converting malic acid into lactic acid), brewers use LAB like Lactobacillus and Pediococcus to increase the acidity of a brew. Like LAB in wine, Pedio and Lacto can sometimes generate diacetyl, which is responsible for the buttery character in, for example, a full malolactic Chardonnay, but which is generally unwelcome in beer. But sour beers are already by their nature a bit outside the box. And while the aromas above may sound awful all together, in sour beer, they just sort of… work. That is, if their presence is carefully managed and controlled.

Over a barrel

Many brewers use oak barrels for aging. Used barrels from wineries are a popular choice. Wineries have an incentive to get rid of barrels infected with Brett, for example, while brewers looking for funk will gladly accept them. Barrel aging of beer is not a new phenomenon, but then again neither is making sour beer. The inside of the barrel also provides a rough surface on which bacteria and yeast can grow and thrive.

In fact, both Brettanomyces and Pediococcus were first isolated from spoiled beer.

Aging beer in wine barrels allows some of the vinous character of the barrel to permeate the beer. Russian River Brewing Company in Santa Rosa, California, (smack between San Francisco and Sonoma) has local access to lots of wine barrels and ages beers in used Pinot, Chardonnay, and Cabernet barrels.

Some brewers even order new oak barrels. For example, Odell Brewing in Fort Collins, Colorado, ages beers for its premium (but not sour) Woodcut series in new oak. Most sour fermentations, though, happen in fairly neutral barrels. Like wine, the barrel environment provides for controlled, slow oxygen transfer. Beers aged in barrel for a long time (more than a year or so) can develop oxidative malt character (mostly trans-2-nonenal, which smells stale, like cardboard) but a little bit of these aldehydes can lengthen the finish and increase the flavor complexity.

In general, a little bit of any of these sour flavors (lactic, acetic) and aromas (funk, oxidative character, maybe even a smidgen of diacetyl) is exactly what brewers are going for. Too much of any one and the beer quickly becomes good for educational purposes only, and brewers don’t have the high alcohol content or low pH of wine to retard growth of unwelcome microbes. For this reason, barrel wranglers at breweries must taste barrels frequently. Also, as any winemaker knows, individual barrels are prone to wide variation, which makes the process even more difficult.

Barrel wrangling

The intrepid brewers who tackle the task of sour beer making require three basic qualities: (1) microbiology understanding far beyond Saccharomyces; (2) well-trained palates for barrel monitoring and eventually blending; and (3) a streak of devil-may-care recklessness. After all, sour beer making is far more demanding than making your normal IPA. Typical ales can be fermented and ready for packaging in as little as two weeks, while a very young sour beer would have been in barrel for almost a year. And the return on investment is not always great. It’s a product that consumers have to be eased into, although craft beer consumers are generally pretty open-minded.

So, why make sour beer then? If time (and physical space in the brewery) is money, are they really worth it? “Craft beer consumers are always looking for what’s next,” says New Belgium Brewing media relations director Bryan Simpson. New Belgium Brewing, one of the largest craft brewers in the country with production approaching 800,000 barrels a year, first started its sour program in 1997 with a sour brown ale called La Folie: “the folly”.

“Wood cellar shepherd” Lauren Salazar runs the NBB sour program and comments that demand for sour beers is “up like crazy” and that NBB “absolutely make[s] money on it.” New Belgium’s sour program may be economically viable because of economies of scale. The Fort Collins brewery is home to over 4,200 hectoliters worth of foeders, enormous barrels that hold thousands of liters of beer. (Foeders generally come from wineries, where they’re often referred to by the French foudre). Foeders save space and generally provide for more consistency throughout a particular batch (i.e., the whole batch is in fewer individual barrels). Their small surface area to volume ratio and constant reuse also make them neutral, imparting virtually no oak character to the resulting beer.

The little guys

While larger brewers benefit from having the capital necessary to fill a room with foeders, smaller breweries making sour beer are making it, well, because they feel like it. “It’s fun. It’s what we drink,” says Andy Parker, senior brewer and barrel room manager at Avery Brewing in Boulder, Colorado, with twenty times smaller total production than NBB per year. However, he does concede “some of it’s marketing.” If adventurous craft beer lovers try a sour beer from a particular brewery, they might (1) see them as innovative and (more importantly) (2) buy some of their other beers.

Eli Kolodny, “A Quality Guy,” at Odell Brewing in Fort Collins, sums up the situation with an especially apt analogy: Baskin Robbins is marketed as having “31 Flavors”, but their best seller is vanilla. They wouldn’t open up a store called Baskin Robbins One Flavor where the only flavor was Rocky Road. “Vanilla pays for Rocky Road,” says Kolodny. Regarding sour beer, he feels, “It will always be a niche,” but talking to the brewers that make sour beer, one can tell that this apparent “folly” is driven by a love of beer and a desire to explore the boundaries of beer brewing, or in the words of Andy Parker, “embracing the chaos.”

Getting spontaneous

Speaking of folly, some brewers go way off the deep end, yielding all control of the barrel to spontaneous fermentations. Destihl Restaurant and Brew Works in Normal, Illinois, produces a series of sours called St. Dekkera. Named after the spore-forming variant of Brettanomyces, acidification of St. Dekkera beers is completely spontaneous. Matt Potts, founder and brewmaster at Destihl, asked about sour beer demand, explained: “We did it because we wanted to do it, not because people are asking.” A small brewpub, Destihl pours roughly half of its sour inventory at the Great American Beer Festival, which Potts sees mainly as a marketing expense, which apparently worked on this writer. Their oldest sour was four and a half years old… until the last of it was eagerly consumed at the GABF.

Maine brewer Allagash goes the whole hog with its Coolship series, where wort (the mix of sugars and other ingredients that eventually becomes beer) is cooled in shallow swimming pool-like containers (coolships) and allowed to pick up whatever microbes may be floating around in the air. This is how lambics are made in Belgium and its success relies on the microbial terroir of the area. The resulting product is a rustic, wild, tart, and complex flavor explosion. Finally, Crooked Stave Artisan Beer Project in Denver, Colorado is an operation completely devoted to wild and sour ales. From 100% Brettanomyces fermentations, to experimenting with horsey, cheesy, and other strains of Brett, Crooked Stave embodies the curiosity of founder-scientist-brewer Chad Yakobson and makes academically interesting beers with complexity that beggar description.

Recommendations

Sour beer brewing is still (and will likely remain) a niche market, always supported by beers that “keep the lights on” (an expression that several brewers used when I interviewed them.) Kind of like George Clooney, who acted in popular films like Ocean’s 11 in order to be able to make artsier films like Good Night and Good Luck or Syriana. Sours are also exceptionally food-friendly, with refreshing acidity and rustic aromas pairing well with cheeses and savory meals, or useful as a curveball aperitif. Craft beer consumers looking for unique, special, limited offerings will delight in the range of sour beers being painstakingly produced at brewpubs and craft breweries across the country.

Of the roughly 200 beers I tasted at this year’s GABF (and for this story), I’ve constructed a list of sour beer recommendations. Categories are quite fluid (after all, brewers don’t really tend to be boxed in stylistically), but these beers are all excellent. Some of them medaled in the 2012 GABF competitions.

Of the roughly 200 beers I tasted at this year’s GABF (and for this story), I’ve constructed a list of sour beer recommendations. Categories are quite fluid (after all, brewers don’t really tend to be boxed in stylistically), but these beers are all excellent. Some of them medaled in the 2012 GABF competitions.

Berliner Weisse (wheat beer with Lacto): Crabtree Berliner Weisse, High Water Berliner Reisse, Blue Star Brewing Barnstormer Easy Sour

Flanders Red/Brown: Lost Abbey Red Poppy (silver), New Belgium La Folie, Avery Oud Floris, Odell The Meddler Oud Bruin

Vinous: Russian River Consecration, Avery Dihos Dactylion

Spontaneous : Allagash Coolship Resurgam, Freetail Brewing Ananke, Rivertown Lambic, DESTIHL St. Dekkera

Brett: Crooked Stave Wild Wild Brett series, Trinity Brewing TPS report (bronze)

Fruit Added: The Bruery Sans Pagaie (gold), Lost Abbey Track 7, Cambridge Brewing Company Cérise Cuvee

Miscellaneous: Union Craft Brewing Old Pro Gose (sour with salt), Choc Beer Co. Gose, Weyerbacher Sour Black, Real Ale Scots Gone Wild (sour Scotch ale), Rock Bottom Sweet Sour Stout, NBB Love Felix (bronze), Crooked Stave Sentience (Bourbon barrel-aged sour quadruple, silver), New Belgium Vrienden (collaboration with Allagash)

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/Mansell-e1262881896388.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Tom Mansell is the Science Editor here at Palate Press and a member of the Editorial Board. He has a PhD in chemical engineering from Cornell University, where he also learned to love the wines of the Finger Lakes. He is also the Science Editor for The New York Cork Report. Tom is currently living in Boulder, CO, where he is a researcher at the University of Colorado. Follow him on Twitter @mrmansell.[/author_info] [/author]