The view is breathtaking: in front of me are the rounded, rocky peaks of the Tofane ridges, while behind me the sharp ridges of Pomagagnon Mountain jut into the sky. I am in the Dolomites, just above the famous tourist town of Cortina d’Ampezzo which is as well known for its jet set crowd as for its historic European aristocracy.

At the end of a forest there is a small clearing, and here, at 1300 meters (4,265 feet) above sea level, you would not expect to find a vineyard. Instead, “Vigna 1350″ (Vineyard 1350) in its 2,400 m² (a little over half an acre) contains 2,000 rooted cuttings of four grape varieties, two white and two red. The field is on a slight incline so 1,350 meters is the minimum altitude and the higher rows reach 1,382 meters. Walking amongst the rows, I note that the vineyard is protected by a high fence where here and there, some curious pouches are dangling. No, they are not pouches. I get close, touch them and see that they are women’s tights, stuffed with something … but what?

“Human hair” says my guide, Fabrizio Zardini, answering my surprised and questioning glance.

“What?!”

“Yes, they serve to keep out deer and badgers. The animals of the forest detect the smell of human beings, and so do not come close to the vineyard.” Obviously, the stuffing is the result of the work of some hairdresser in Cortina d’Ampezzo: an unusual trick, but definitely effective. Just one of the innovations needed to grow grapes here.

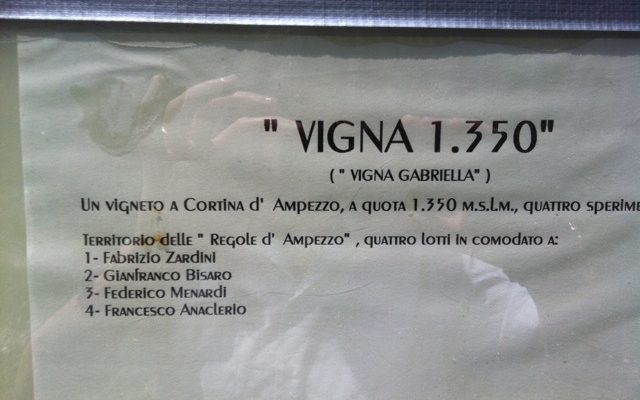

Vigna 1350 is both a challenge and a scientific project: a few friends, very passionate about viticulture and wine, are trying to demonstrate that it is possible to grow grapes in the high mountains. The group is comprised of winemakers Fabrizio Zardini and Gianfranco Bisaro; Francesco Anaclerio, director of the Rauscedo experimental cooperative nursery (VCR); and agronomist Federico Menardi Comin, entrepreneur and wine lover.

It ‘s a kind of back to basics, because according to many researchers, the wine grape species vitis vinifera comes from a mountain environment in the Caucasus or Armenia. Here at Vigna 1350 the rooted cuttings were planted on June 2, 2011, with a density of 6500/ha: in September 2012 they had their very first, small bunches.

“Bringing viticulture to Cortina was a tribute to its origins, because the vine is cultivated in areas adjacent to the Cortina basin,” Zardini explains. “Furthermore, it is likely that in some primitive form it was also present until relatively recent times in local, family vegetable gardens.”

In addition, by planting this vineyard the four friends (two of whom were born here) are carrying out an interesting study on the effects of solar radiation at high altitude on the grape.

Why do you think it’s so important to study this aspect so deeply?

“Because at this altitude, compared to the usual area of cultivation of the vine, we have 1,200 watts/square meter, whereas in lower zones we have only 800-900 watts /square meter. Here, the main irradiation is ultraviolet, and these rays greatly affect the development of the aromatic part of the grapes.”

I guess it’s a challenge to cultivate a vineyard, up here – I comment to Francesco Anaclerio, who is studying a container with many new rooted cuttings that are ready to plant.

“Well, frankly it is tougher to establish it than to manage it. When the plants are very young the risk is that they won’t survive the winter. Last winter we had 20 days at -20 Celsius degrees (-4 F), day and night, but without a protective mantle of snow. The soil had a temperature of -6 Celsius degrees (21 F). We lost 30% of the rooted cuttings we had planted — but most of them survived.”

What vines did you plant, and why?

“Inspired by the experience wine producers have had in Chile where they grow grapes at heights greater than ours, we chose varieties with short growing seasons and with greater resistance to the cold temperatures. We planted Incrocio Manzoni bianco (a cross of riesling x pinot blanc), palava (Muller Thurgau x traminer), André (blaufrankisch x St. Laurent) and petit rouge (the most important native red grape in Val d’Aosta).

“There is no need for a lot of vineyard treatments, because here the ultraviolet rays block cryptogams [fungus and other vegetation that reproduces without seeds]. When the radiation decreases, that is, after the middle of September, we noted last year some signs of late downy mildew but it could no longer do damage, because the grapes were ripe.”

The project “Vigna 1350” is funded by the four friends, and is also supported by technical sponsors who provided necessary equipment including rooted cuttings, steel wires and poles, and even the control unit for the recording of climate data.

“The purpose of this vineyard is not only to study the behavior of the vines in such extreme conditions,” reaffirms Zardini. “But it’s also a way to draw attention to the problems of protecting forests and restoring areas that have been partially or totally neglected.”

Anyone who cares about quality viticulture and loves mountains can share this project from anywhere in the world: just adopt a vine or a row. You can choose which rooted cutting to adopt by purchasing a certificate; it will be registered on the official web site (which is unfortunately only in Italian)

The vineyard’s fence will carry the names of the individuals or companies that have signed up for “adoption” and they will also receive a newsletter informing them of milestones during the year. And if you want to take a look right now, there is a small window open here.

It is trained on the vineyard, so you see the plants in real time (there is a gap of a few minutes). The environment itself is of great beauty: the highest vineyard in Europe, set amidst the Dolomites, a Unesco World Heritage Site.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/162f729-e1266674226608.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Elisabetta Tosi is a freelance wine journalist and wine blogger. She lives in Valpolicella, where the famous red wines Amarone, Ripasso, and Recioto are produced. Professionally, she serves as a web-consultant for wineries, and in her free time writes books about Italian wines. She is also a contributor to Vino Pigro.[/author_info] [/author]